Robyn Rosenstruss would visit her grandmother in Balmain, Sydney, where the elderly lady would gesture to the small timber chest of drawers which took pride of place in her home. ‘That’s Jimmy’s Box’ she would say. Robyn the child never knew who ‘Jimmy’ was – she simply accepted that he and the box he had carved were very important to his sister Margaret Nobel (nee Fettes). Later Robyn became interested in ‘Jimmy’ and continued to ask herself where and how her great uncle, Chief Engine Room Artificer James Alexander Fettes died.

On 14 September 1914, Australia’s first submarine, AE1, simply disappeared and for generations of relatives of the 35 crew there was no closure. The disappearance of HMAS Sydney was Australia’s biggest naval mystery, one which has been resolved and the ghosts of those onboard laid to rest. The disappearance of AE1 was Australia’s first naval tragedy has been the most enduring.

It was a brave decision for Australia to include submarines in its nascent navy in 1913 because their capabilities were still largely unknown. The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) purchased two E-class boats built by Vickers-Armstrong in England. They were 55.17 metres long, with a top surface speed of 15 knots and submerged speed of 10 knots. Propulsion depended on two 8-cylinder diesel engines. They were armed with 4 x 18-inch torpedo tubes. Crew consisted of three officers and 32 sailors. Due to a shortage of Australian qualified submariners, it was necessary to loan some Royal Navy (RN) personnel to make up the crews. Their service was arduous, human habitability had received only minimal consideration. The boats were re-commissioned with an A in front of the E, hence AE1 and AE2. The journey to Australia was an amazing achievement breaking all submarine long distance records. One crew member described the journey as one filled with.

Mechanical difficulties and mishaps overcome by hook and crook, the miles were pushed astern, the weariness of it but lightly relieved by a few days in ports of call.

Passing through the Mediterranean the heat within was so terrible it was decided to paint the boats white. The submarines, repainted black, entered Sydney Harbour in time for Empire Day celebrations, 24 May 1914. The voyage had taken 83 days, 60 of which were spent at sea. For some of the 20,800 km the boats were towed by their escort but 14,400km were under their own power. The London Times declared it ‘the most remarkable yet performed by a submarine’.

More than half the boat crews were loaned British officers and sailors, but it took little time for some to decide to make Australia their home and to convert their return trip to England to ship passage for their wives and children. Able Seaman Fred Dennis immediately liked what he saw, transferred to the RAN and, sent for wife Florence and children Charles, Catherine and Gwen to join him in this ‘wonderful country’. Able Seaman Henry Fisher decided to bring wife Lily and children Eva, 5; Arthur, 3; and six-month old George from Portsmouth to Sydney. Soon 18 AE1 crew called Australia home and 32 children were now RAN dependents.

The crews had bonded during the long journey and the Australian-born did their best to invite the newest Australian crew to their own homes. Given the difficulty and infrequency of long-distance travel this was not possible for Engine Room Artificer John Messenger. John, known as ‘Jack’ barely got home on leave himself before being recalled to duty. Jack was from Ballarat, Victoria. To some it seemed strange that this country boy would join the navy, but Jack’s reason was not entirely motivated by patriotism. He had got into a fight in a Melbourne pub and beat up the other so badly it was believed the man would not survive. Jack’s uncle hastily signed him on as a seaman onboard a merchant ship due to leave for England. His adversary survived and on arrival in England Jack joined the RN. When he heard, volunteers were needed to crew submarines bound for Australia he was first in line.

Elizabeth Jarman opened the door of her Dookie, Victoria, home and was overjoyed to discover her son Jack waiting. He seemed so much more mature and had certainly adopted the more colourful ways with tattoos on both arms. Jack Jarman had joined up, like so many others, so that his salary could help support a family in the pre-welfare days of the first decades of the 1900s.

Britain declared war against Germany on 4 August 1914 and Australia’s navy was immediately despatched to capture German Pacific islands and flush out any German warships which may be stationed around New Guinea, then a German protectorate. The submarines were undergoing maintenance in Sydney and were delayed. Unseasoned by war their crews were anxious to join the fight. One wrote, ‘Our self-pity was extreme’. The submariners could never have imagined how ‘extreme’ their part in World War 1 would be.

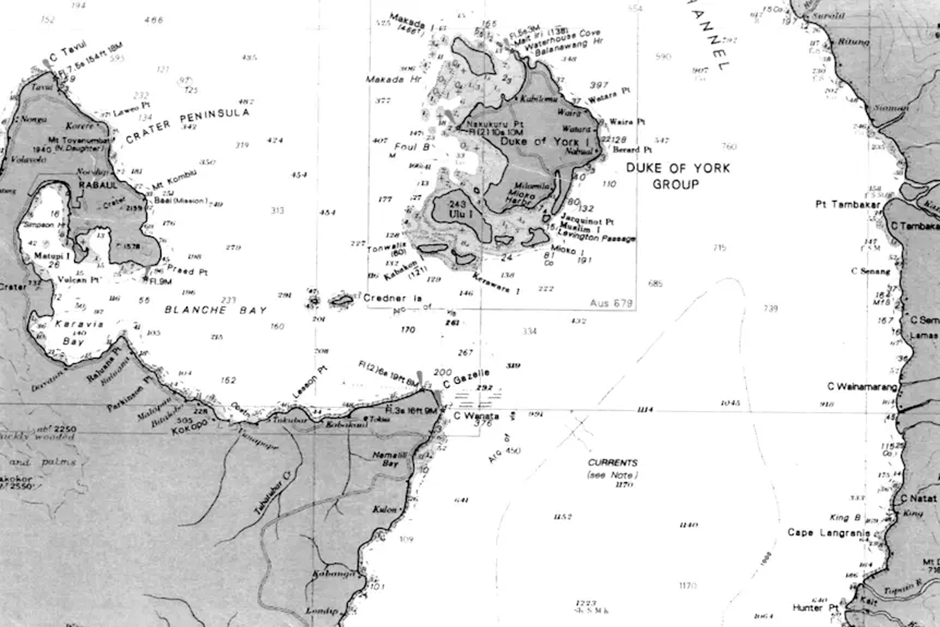

On 2 September the submarines left to journey north to Rabaul. In 1910 the German colonial government had established its administration from Herbertshöhe (today’s Kokopo) to Simpsonhafen, New Britain, which was renamed Rabaul, meaning mangrove

in Kuanua (the local language). The British naval presence was established when they arrived in the splendid Simpson Harbour, having broken yet another world record, steaming 1931km without an escort.

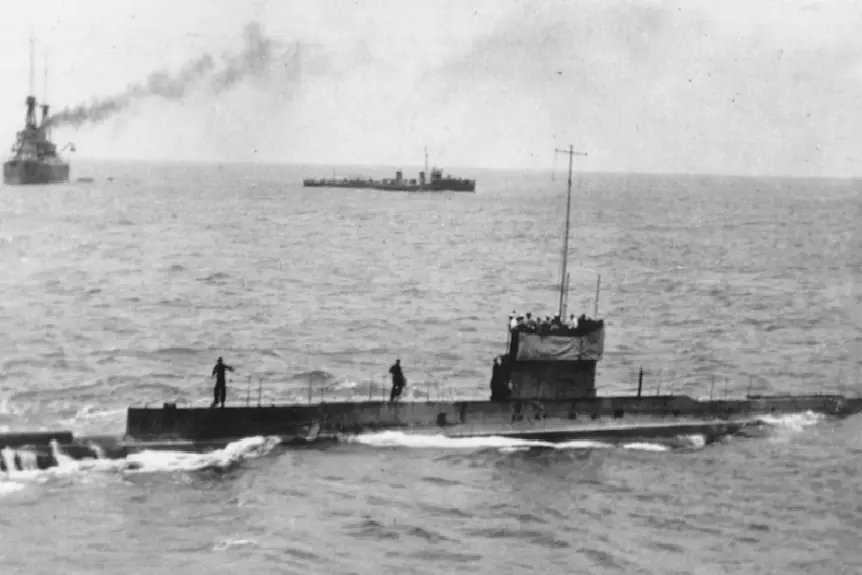

On 14 September at 7am AE1 left Rabaul on patrol in the company of HMAS Parramatta. The warship diverged its course and lost sight of the submarine when AE1 was approximately between Waira and Jaquinot Points in St George’s Channel off Duke of York Island.

The first search was delayed but it and subsequent searches found no trace of AE1 or its crew of 35. A crew member of AE2 wrote:

We fear the worst, her loss we mourn, gone forever from our sight … the sense of loneliness felt in AE2.

Whilst the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 is commemorated as the ‘blooding’ of Australians in what was to be a terrible war, the loss of AE1 on 14 September 1914, was in fact the loss of the first Australian military unit, and combined navy and military forces had already exchanged fire with German troops on the New Guinea mainland during the first months of the war. AE2 voyaged to the Dardanelles and was the first submarine to breach Turkish defences, enter the Sea of Marmara and threaten the Turkish navy. Under attack the crew scuttled their submarine and abandoned their boat on 30 April 1915. They spent the remainder of the war as POWs with several dying in captivity.

For the relatives of AE1 there was the agony of not knowing. Families arriving from England to rejoin their husbands and fathers were met only to be told they were missing. Personal effects held in storage on a support ship were returned to next of kin.

Elizabeth, the mother of Jack Jarman wrote:

“Thank you, these little trifles of his personal belongings mean a lot to me. The last I shall ever have to remind me.”

The mother of Petty Officer Smail of Melbourne wrote:

“They are my dear boy’s. Little did we think when we parted with him we would never see him home again. The thought is terrible.”

The handmade wooden set of drawers ‘Jimmy’s box’ was sent to the Fettes family.

For many decades there was an Australian Government reluctance to answer the question”What happened to AE1 and where do the crew lay?”

Individuals instigated private searches. Later when in the general area of the disappearance RAN ships searched but without the necessary equipment for deep water. There had never been oil or fuel or wreckage which made it a mystery and eliminated catastrophic explosion, or even collision with another ship or reef whilst submerged. The crew presumably remained entombed in their submarine at the bottom of the ocean.

Fascinated by this mystery I visited Rabaul, researched and interviewed. I joined AE1 Inc., an enthusiastic group of relatives and supporters, and became their honorary publicity/media officer. My book The Mystery of AE1: Australia’s lost submarine and crew, was published in time of the centenary of Australian Submarines, launched at Holbrook in the shadow of another Australian submarine, by my elder son, himself an ex-submarine engineering officer.

I was invited by the Chief of Navy to give an address in Rabaul at a ceremony marking the centenary of the loss of AE1. Melissa Doyle and her television film crew hired a speed boat and we sped across the ocean to where I believed the submarine lay. As we neared the point HMAS Yarra was conducting a search. 35 red poppies were placed in the water – it was a very memorable day.

In December 2017 a new search, using the vessel Fugro Equator, finally located the wreck of AE1 in 300 metres of water off the Duke of York Island group, close to where I had predicted. On 21 December 2017 the Australian Government formally announced that the exact location of the wreck would not be publicly disclosed. In April 2018, an expedition was conducted using the Research Vessel RV Petrel to perform a detailed Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) survey of the wreck of AE1. The ship’s ROV, fitted with high-definition video and stills cameras, undertook a comprehensive, non-invasive inspection. From the 8000 digital still images collected a full photogrammetric 3D model of the entire wreck.

It seems the crew remain within. Analysis continues to understand ‘what happened to AE1’. Items like ‘Jimmy’s box’ will forever be treasured by generations.