Albert ‘Bert’ Adrian Stobart was born on 11 April 1921, in Sandringham, Victoria, to John and Beatrice. Initially hoteliers in the gentle green English countryside, his parents migrated across the world to the strong colours of Australia. The family moved to the Melbourne. They were a devout Protestant family, Bert, was the youngest of seven children. They had only returned from church when there was a radio announcement that Australia was at war.

The RAAF appeared to offer a more glamorous, a cleaner, safer war. By 1940 cinema newsreels highlighted the heroics of Spitfire pilots while typically downplaying the brutal cost in lives. Bert Stobart was disappointed at not being streamed ‘pilot’ but intended making the most of his service as a Wireless Operator Gunner. Bert had little difficulty in the physical side of service life – the marching, parades, and physical exercise under the ever-watchful eyes and loud, colourful language, of drill instructors. The theory component proved insurmountable. He had trouble with Morse Code, those dots and dashes seemed to blend, in an unholy mess. His training was extended to another month. Bert quickly acquired the nickname ‘Stoppy’ due to the Australian preference of either shortening or lengthening names, whichever seemed easier. It seemed rather appropriate given his non-speed with Morse.

He dropped the wireless part and was recategorized ‘Gunner’. His posting to Bomber Command England came quickly and there seemed too little time, too much to say, but no way to say it to family standing wharf side, particularly Noel, the girl he had fallen in love with. The war delayed their plans to marry, but they were engaged.

Training in England was busy and dangerous. The world was moving fast and crewing up traumatic. Pilots got to chose their crew and Bert was hopeful he would find himself in a good crew, because a bomber crew was only as good as its weakest link. He hoped a particular pilot would choose him and was crestfallen when the man chose a different rear gunner. That crew was killed on its first operation. It was not the last time that fate would be kind to Bert Stobart.

Robert Barr McPhan RAAF from the small NSW Central Coast settlement of Kanwal, introduced himself. The Bomb Aimer was Sydneysider, John Andrew Spence, RAAF, the Mid-Upper Gunner was Ian ‘Jock’ Hilton (RAF) and Robert Freeman (RAF) from Oxfordshire, was the Wireless Operator. Another Englishman, Sgt Michael ‘Simmo’ Simpson (RAF) from Middlesex was chosen to be navigator. On their conversion to Lancaster Bombers Sgt Thomas McCulloch (RAF) became their Flight Engineer. They were an interesting mixture of accents, ages, and personalities and needed to bond quickly to survive.

Their training had a new urgency as the air war extended further into Europe. They were posted to RAAF 460 Squadron. On the day they arrived they were told there was no aircrew accommodation available – quarters were full. The statement which followed was delivered with alarming calmness: Don’t worry about it, ops are on tonight, you’ll get accommodation tomorrow night. The following morning after a raid on Cologne, a Lancaster crew did not return. Belongings were cleared away, fresh sheets placed on the beds and the Stobart crew moved in.

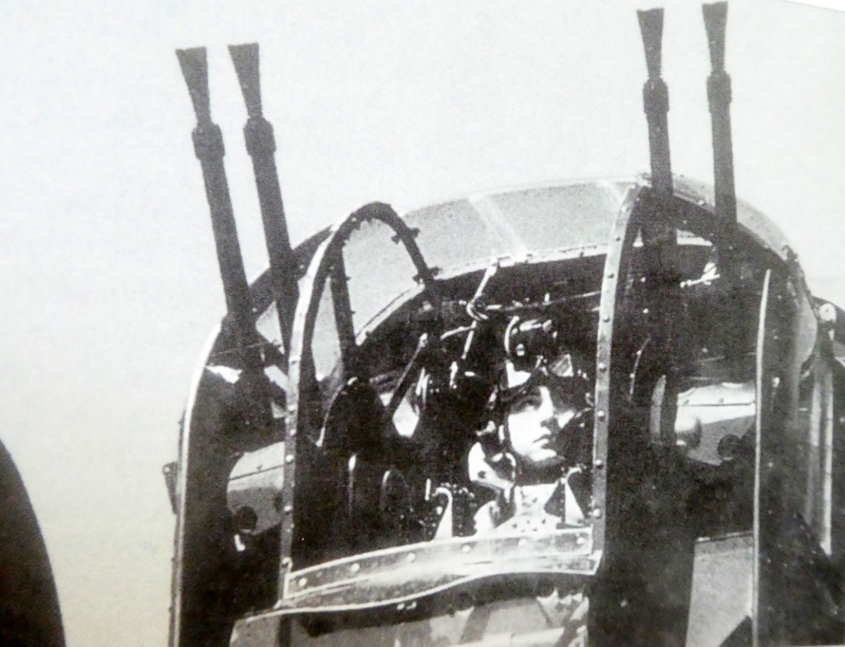

It took little time before any sense of ‘glamour’ disappeared and for the feeling of fear in the pit of the stomach to assert itself each moonlight night as they climbed into their Lancaster. Bert had the coldest and most precarious of positions. It was not for the faint-hearted or weak stomached. The rear turret followed all the aircraft movements, pivoting rapidly on its centre of gravity horizontally and sideways for him to scan the skies for enemy fighters, who preferred to shoot the rear gunner first. There were terrible stories of rear gunner turrets disappearing altogether or rear turrets having to be hosed out of what was left of the airmen who had manned it.

It was the night of 3rd/4th September 1943. It was the crew’s 11th operation. With 30 operations needed to be completed for a tour to be over, they had a way to go. Unfortunately, the target this night was Berlin. That was a long flight from England, being subjected to heavy anti-aircraft fire and enemy fighters. Lancaster EE132 had just crossed the Dutch coast at 17,000 ft (5182m), when their world disintegrated. Bert would say: ‘I didn’t see it, the mid upper gunner didn’t see it, nobody on the aircraft saw it’.

The starboard engines burst into flames which spread rapidly along the wing. The bomber began a downward spiral, they had been shot from below by an ME110 night fighter. McPhan’s garbled voice came on the intercom asking: ‘Who’s hit?’ before communication dropped out. A light with ‘P’ displayed above each crewmember, indicating the crew should abandon aircraft. Bert centred his turret, crawled into the main fuselage, and grabbed his parachute. Hilton, the middle upper gunner was injured and trying to extract himself. With difficulty Bert hauled himself up and freed ‘Jock’ from the turret. As they began to slide down the fuselage Bert assisted the other gunner to harness his parachute. ‘We were downhill, running at this stage, you know with the flames coming out’. Bert realized the Lancaster had lost a lot of altitude and was likely down to around 10,000 feet (3,048m). He kicked out the rear door and watched Hilton fall through the opening. Bert paused, he curiously felt no panic: ‘Should I go up and see what the rest of them were doing, if everything was right up front?’. He climbed as far as the main spar and was struggling to get over it. Something clicked in his brain. ‘I thought ‘’Oh well, we’ll probably see them on the ground … I gotta get out”’.

The drill practiced was to kneel, carefully somersault out of the aircraft, count slowly to seven, or was that ten? to clear the bomber, and when on one’s back, place an arm over the parachute enabling the elastic bands to pull the wrapping away, and the spring to eject and release the canopy. That was the drill. Bert released his grip from the main spar, fell down the fuselage and out of the Lancaster. He only just cleared the fin and pulled the ripcord. There was a tremendous jerk and horrifying sound of stitches being torn on the heavy leather straps – ‘Christ let them hold’, shot through his brain. The ground came up too quickly. There was no time to complete those instructions that went something like, taking the initial landing on relaxed legs, pulling yourself into a ball, and rolling to the left or right as preferred. Bert released his parachute harness too soon, landed with a terrific thud and knocked himself out.

He wasn’t sure how long he was unconscious. Struggling to his feet, his parachute was nowhere in sight and he realized he had suffered a concussion. He felt decidedly ill. There was no bomber, no other crew, and his confused brain could make no sense of what had happened – ‘Had he been told to bale out … If so, where was everyone … was he in Holland?’. Bert had seen the Lancaster flying level but on fire. ‘I thought I would see some of the crew, but I didn’t’. On 3 September 1943 Lancaster EE132 exploded on impact, 3,280 feet (1000 m), 24 miles (39k) south of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Only Bert and Hilton had survived.

Bert began to wander; ‘I felt so sick’. The uniforms were easily recognizable and the German soldiers were none too gentle as they bundled Bert into a car. He still felt squeamish and thought:

This will be good, I’m bound to be sick, and I’ll puke all over them. But I didn’t, I didn’t puke, maybe it was just as well, I would have got belted.

The next days were ‘not nice’ but the ensuing months and years decidedly worse.

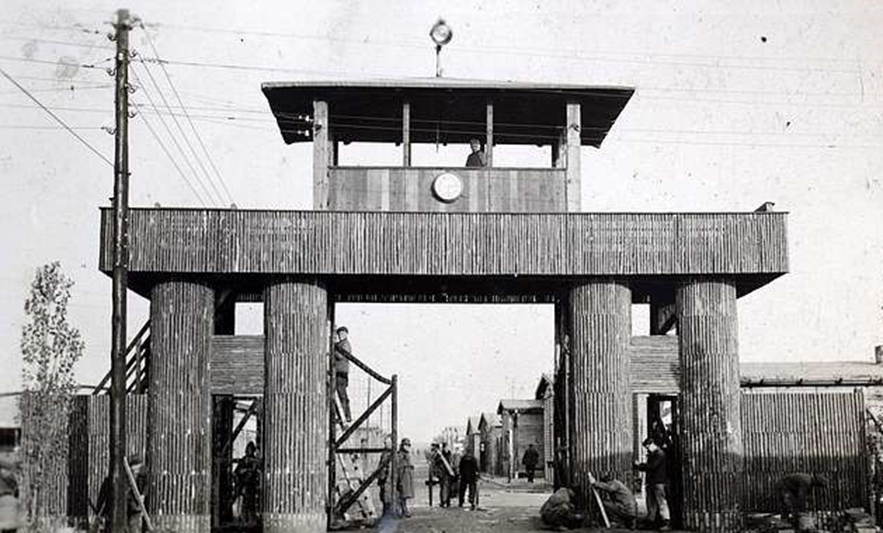

The imagined career in the RAAF had never included being a Prisoner of War of Germany. so adapting to the life in Stalag IVB was never going to be easy. Members of the military taken prisoner arrived in camp with belongings. Australians shot out of the sky arrived with nothing but what they stood up in. It was harsh. Only due to the generosity of other aircrew who had been in camp for months was Bert able to secure a few belongings. German rations were shocking. They received something called soup, weak potato swill with a bit of horsemeat.

‘You’d move the maggots aside because they used to go with your soups.’

When they were given a small loaf of bread this was carefully divided into 24 slices by their group of four. Each group needed to ration their scarce resources, save as much as they could in case things got worse – and they did. If they were fortunate their single meal of the day was four thin small slices of bread, 2ozs of bully beef, two potatoes and four spoons of barley. Red Cross parcels kept the airmen alive, and then they stopped coming as the Allies advanced.

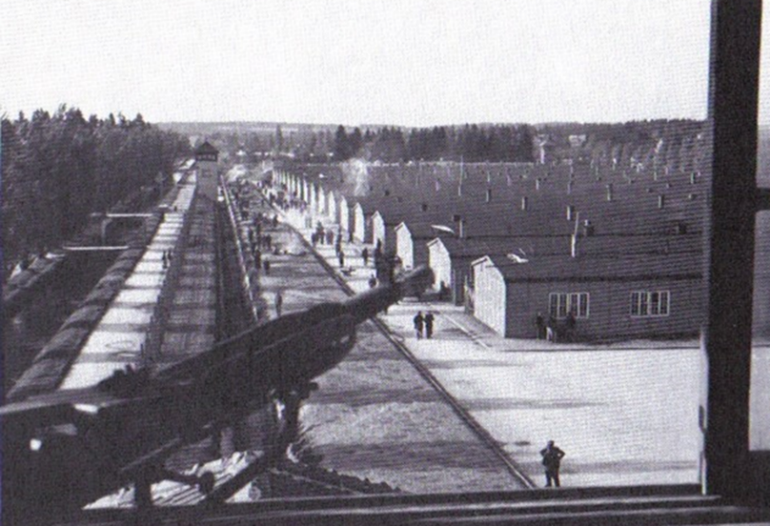

Aircrew of all nations were treated differently as POWs. They were secured in a special tight confine unto themselves. They were not allowed to be included on work parties, which allowed POWs to bring back wood, barter, and ‘collect’ additional food. The German Government believed that should the aviators escape, they could return to bomb again. His hut with 200 odd individuals ‘felt crowded, almost overpowering’. His bunk, one of three tiers, offered a thin mattress and a palliasses, full of straw and a small wool covering, which offered little respite from the numbing cold of the northern hemisphere winter. Huts had window glass missing so they bordered them up with Red Cross parcel carboard. The coal allowance for the single hut stove diminished.

British authorities had told airmen: ‘It is every POWs duty to try to escape’, but there was no escape for aircrew confinement at Stalag IVB. Inspired escapes occurred from other POW camps but one from Luft III resulted in the murder of the recaptured. The news of the Allied advance had heartened Bert Stobart but progress was slow and more and more POWs arrived crowding into spaces. The already scarce food supplies had to feed even more mouths. New aircrew brought stories of their fellows landing by parachute from a burning aircraft only to be killed by angry civilians.

Disease became prevalent. As the Allies pushed further into Europe life became more dangerous. Guards became more invasive and violent, searches more frequent and POWs made to stand out in the snow for hours. Anyone seen to be approaching the barbed wire was shot. Any perceived indiscretion was punished. ‘At the back of the mind of any sane POW is fear.’

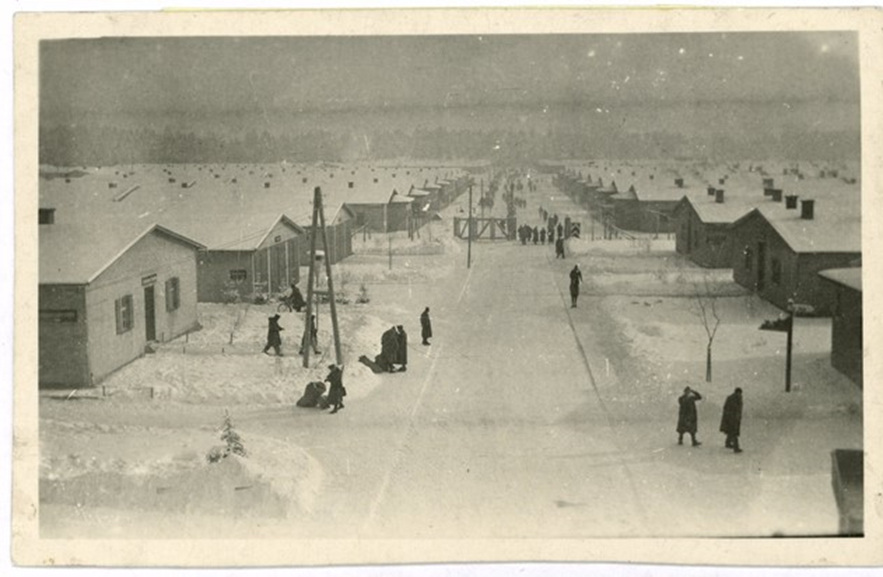

The winter of 1943 was bad, but the winter of 1944 was the coldest in decades. With freezing conditions and scarce food one Australian aviator wrote in his diary:

Another lousy day … couldn’t be bothered getting out of bed … bags of rumours – all baloney in my opinion.

The same advance meant more prisoners, POW camps were so overcrowded tents were erected in the grounds offering little respite from the freezing conditions. Stories told by new POWs spoke of how aviators parachuting from burning aircraft were being murdered by civilians.

To keep himself going Bert ventured as far as he could to meet other POWs. He had a book which he labelled ‘My Trip Aboard’ and he beseeched everyone to draw, write, paint in the book. In doing this he met an artist who agreed for a trade, that he would paint a colour portrait of Noel from the small black and white photo Bert carried.

As Germany lost more and more ground, POWs were made to march through deep snow hundreds of kilometres away from the advancing Allies. These death marches took a horrendous toll on body and soul. Some marches only ended when friendly forces overtook them – thousands died, from hunger, from the weather, or shot where they fell. Bert Stobart realised how lucky he was that Stalag IVB was sufficiently deep in Europe not to require evacuation.

They thought they were free when the Russians arrived but instead were used as pawns in the political battle for territory. British troop trucks were turned away by Russian machine guns entrenchments. Under the night sky Bert and friends escaped and began the long walk to freedom. Authorities were shocked at how much these vibrant strong aviators had lost their weight and health and months were spent rehabilitating, ‘fattening up’ in England before they were returned home to Australia.

They left Australia, the finest of youth – many still teenagers. They believed they were invincible. Imbued with patriotic fervour, they were determined to fight against evil, defend freedom and the British Empire. Seduced by Hollywood’s gallant depiction of World War I aviators, and Biggles books, they believed there was glamour and safety in joining the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). The reality was entirely different. They became RAF Bomber Command fodder in the dangerous skies over Europe. Bomber Command aircrew suffered the highest of casualties. Of the total of 125,000 aircrew 57,205 or 46 per cent, were killed. A further 8,403 were wounded and 9,838 were shot out of the fury of the sky into the hell of German POW camps – a total of 60 per cent of all operational airmen. Of the 10,000 Australians who served with RAF Bomber Command, 3,486 were killed and 650 died in training accidents, the highest Australian fatality rate of any unit in WWII.

Bert married Noel as soon as he could. He spent much of his life fighting for concessions for POWs of Germany and families. He rose to Vice President of RSL Victoria. Pride of place in their home’s foyer was given to that painting, of a young Noel painted in a POW camp in Germany. They died within months of each other. Noel Margaret Georgina Stobart died on 28 January 2015 aged 94. Albert ‘Bert’ Adrian Stobart OAM died 16 September 2015 aged 94.

Read more in the book, Fury To Hell. Click here