It was in the blood, the military heritage thing. She had been raised on the stories; khaki uniforms had filled her home. Her father was born in Ireland in 1876 with the grand name of Harry Lort Spencer Balfour-Ogilvy. From a very prominent Renmark family he was a ‘cattle dealer’ when at 25 he enlisted in the, South Australian Commonwealth Continent for service in South Africa, on 21 January 1902, one of five Balfour-Oglivy brothers who served for the British cause. Harry and his brother Walter were managing one of the family’s agricultural holdings, the 2,500 hectare ‘Paringa’. They were about to set out on horseback for the Adelaide recruiting office when one of their stockmen asked if he could join them. His name Henry Harbord Morant, known as ‘Breaker’. All being excellent horsemen meant enlistment was rapid, as was their embarkation. For the unfortunate ‘Breaker’ Morant the war ended ignominiously, in front of a firing squad. Lieutenant Harry Balfour-Ogilvy returned the most highly decorated South Australian Boer War veteran, awarded the Queens Medal 5 clasps and Distinguished Conduct Medal, and mentioned in despatches by Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener.

His heroics continued into another war, the war of 1914-1918. He was appointed a Captain in the Australian Imperial Force, Tropical Force Unit, in charge of native Affairs Rabaul, in the former German New Guinea in 1915, moving frequently to flush out remaining pockets of German resistance. As a Major with the 3rd Infantry Battalion Rabaul Garrison, he brought a detachment of native constabulary to Vila in HMAS Una rendering: ‘a very important element in operations’ and receiving further commendation for:

His unflagging energy, his coolness, his tactful handling of natives was beyond praise. His assistance was invaluable.

Born in 1912, the fourth of five children Elaine, known by family as ‘Lainie’ only knew her father as a fleeting figure in military tunic during her earliest years and even when he returned from New Guinea in November 1918 his presence was ephemeral as he pursued the family rural interests throughout South Australia. By 1928 she was in boarding school displaying a faultless combination of her father’s high achieving genes and the grace and genteel qualities instilled in her by her mother Jane. She excelled, as a member of the Adelaide Woodlands School dramatic and debating societies, representing the school in hockey as well as proving an excellent swimmer and tennis player. Her voice resulted in an invitation to join the Adelaide Choral Society.

Lainie chose nursing as a career and by the end of 1934 and three years study and training at the Adelaide Children’s Hospital she was awarded the hospital’s silver medal. With war again in Europe she, with her brothers Douglas and Spencer, enlisted.

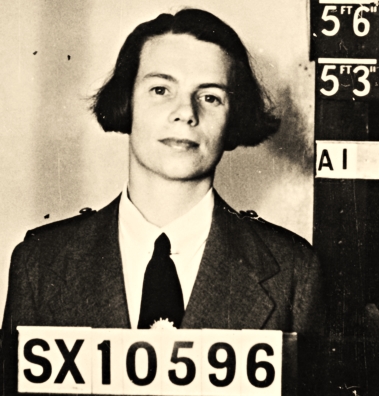

The writing is extremely neat and precise on the ‘Australian Military Forces Attestation Form’, as one would expect from the high achiever who was Elaine Lenore Balfour-Ogilvy. She was a ‘trained nurse’ who was closing in on her 29th birthday and ‘single’. Just as nurses had been the only women to serve with the Australian military in the previous war, in 1940, only unmarried nurses could enlist. The question: ‘Have you previously served on active If so, where and in what arm?’ was entirely superfluous, but officialdom was yet to catch up with women in its ranks and Lainie was desperate to:

Swear that I will well and truly serve our Sovereign Lord, the King, in the Military Forces of the Commonwealth of Australia.

The life of Staff Nurse Balfour-Ogivly was moving at a fast pace. By January 1941 much excitement as she was ‘kitted up’ with her tropical uniform before proceeding home on pre-deployment leave. She was to embark overseas for Malaya. Military command believed the Malayan peninsular, and the ‘impregnable’ island of Singapore were British strongholds against any Japanese aggression. Harry beamed as he watched his daughter in military uniform leave for the tropics as he had done decades ago. Little did he or Jane realise as they waved farewell at the Adelaide train station that they would never see their daughter again.

For Elaine pride was a glorious emotion to be enjoyed that typically hot late January morning in 1941. Boarding the grand Queen Mary in Melbourne was heady stuff. She was now part of the 2/9th Field Ambulance, full of patriotic fervour and belief in her ability as a Staff Nurse. Awkwardness came when she was asked to sing at a cabaret night in front of the thousands onboard. Her voice delighted the audience, and she was begged to sing at all concerts thereafter. Elaine declined, she was a military nurse, not an entertainer. The long sea voyage enabled familiarity with other nurses and by the time the Strait of Johor were approached, firm friendships were established.

From left back row: Jess Dorsch, Peggy Wilmott, ‘Mina’ Raymond, Elaine Balfour-Ogilvy, Peggy Farmaner, Front: Shirley Gardam, Irene Drummond, Mavis Hannah. Only Sister Hannah returned to Australia.

Singapore was as exotic as anticipated but there was barely time to acclimatise before the nurses were broken into contingents with Elaine’s entrained and crossed into the Malayan Peninsular. British High Command was in denial concerning the pending threat. British colonial high society continued as it had always done, and the nurses were in high demand at social events and as dancing partners.

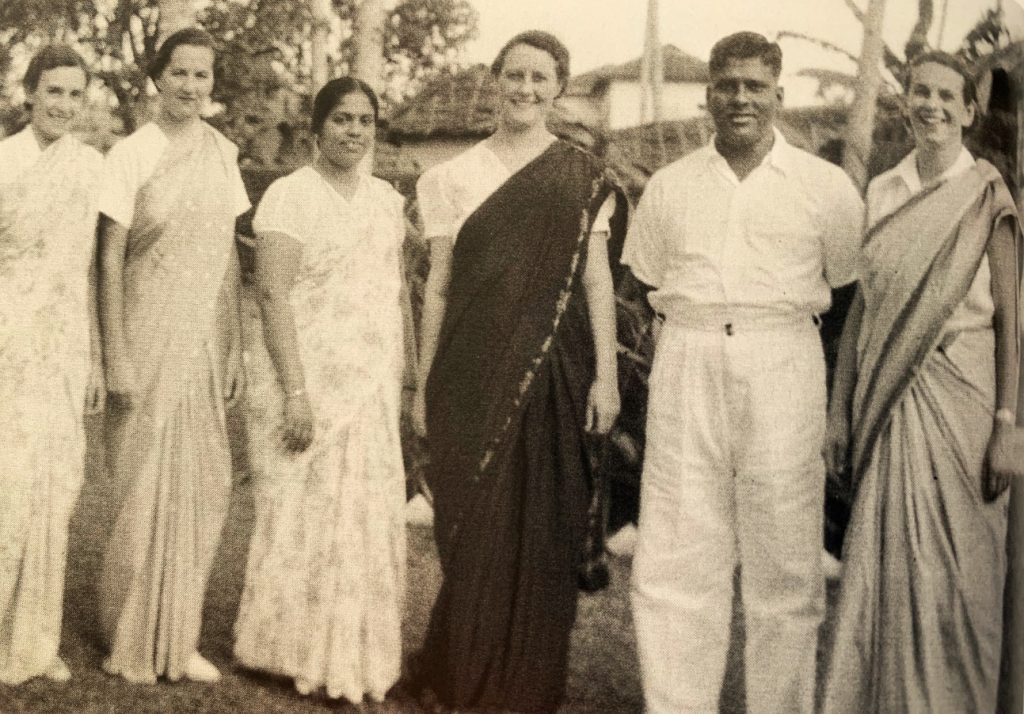

Dressed in sari ready for a social with the Indian community, Elaine is far right.

The perfect world of music and merriment dissolved rapidly into one of chaos. British High Command proved as inept as it was arrogant. Malaya was invaded on 8 December by the Japanese 25th Army. Pearl Harbour was bombed as was Singapore. The wounded filled the hospital. In November during the hurried evacuation of Malaya based medical staff and patients Lainie fell over a water pipe and fractured her left fibula. The army casualty report read that the broken leg was ‘sustained on duty with no blame to S/N’ but Elaine was annoyed this curtailed her duties at a time when the military situation was increasingly grave. Now not only was she a member of the 2/4th Casualty Clearance Station in Singapore but was herself a casualty on restricted duties. She was still in blaster when on 3rd February Japanese artillery commenced shelling Singapore at will. By 8 February the first wave of Japanese troops crossed the Johor Strait into Singapore.

The decision was made that the Australian Army nurses were to be evacuated in the coastal steamer Vyner Brooke on 12 February 1942. As with all military decisions made in Singapore it was too little too late.

Sixty-five nurses, civilian women and children and wounded soldiers without supplies other than one case of tinned food on a boat insufficiently manned and a top speed of 15 knots, made for an easy target for Japanese bombers on the hot and humid morning of 14 February 1942. The boat sank quickly and just two lifeboats were not holed. Sister Ellen Mavis Hannah remembers Elaine Balfour-Ogilvy ‘calling out to me … she was a strong swimmer’ telling her to swim to the island. But Hannah could not swim and would spend three days in the water clinging to flotsam before being washed ashore near Muntok. She was fortunate ‘twelve sisters were lost by drowning’. Hannah became a Prisoner-of-war (POW) and returned to Australia in 1946, ‘because I couldn’t swim’.

One lifeboat was never sighted again, the other containing nurses and wounded soldiers beached on Banka Island. Soon there was a large group gathered on the sands of Radji Beach. Lainie was amongst them having swum ashore despite still not having regained the full strength in the leg she had broken in November. The group realized their situation was hopeless and an officer was sent into the local town, to surrender to the Japanese occupiers.

Captain Orita Masaru arrived with a detachment of heavily armed soldiers. The male prisoners, including the wounded were ordered to the far side of the headland. The nurses heard shots and the Japanese returned, wiping blood from their bayonets. It was the spirited Elaine Balfour-Ogilvy who spoke, suggesting that they should all run in different directions to at least make the inevitable more difficult. It was too late, and the nurses were ordered to line up and march into the ocean. Matron Drummond was heard to say; ‘Chins up girls. I’m proud of you and I love you all’ before the machine gun opened fire.

The 12 April 1945 notation on the ‘Officer’s Record of Service’ for Lieutenant Elaine Balfour-Ogilvy reads; ‘Previously reported Missing believed Killed now reported Missing and for official purposes presumed to be Dead’. In December 1945 the final notation was written; ‘Deceased whilst POW. Executed by Japanese 16 February 1942’.