It all started with a rather beaten up discarded painting.

It was a brown pen and ink painting of a mine shaft, with the signature W.Carter 1979. No one in the auction paid any interest but history attracts historians. What was more architectural artworks are complex and unusual. The framed painting 44cm x 61 cm I purchased for the princely sum of $18 – the minimum price. There were some weird looks but historians are used to being looked at weirdly, those rolling eyes and the mutters, ‘who would want to stick that on their wall!!’—Ahhh but the history and the story waiting to be learnt. Little did I know what an adventure this ‘boring, unloved’ painting would lead me on, to the dark depths of a mine no less.

Scratching away the spider webs and grim revealed the title ‘Central Deborah Mine, Bendigo’. As I was due to give the address at the annual POW Commemoration Ceremony, Ballarat, Victoria, I decided to do some research on this particular Bendigo mine and ask the Bendigo Historical Society, if they were interested in my donating the painting.

The wonders of the internet. The Central Deborah Mine, Bendigo had a wonderful history, and a wonderful present. It must have been karma because the Bendigo gold rush was started by a woman, one Margaret Kennedy. In 1851, Mrs Margaret Kennedy was washing clothes in the Bendigo Creek when she spied a gold nugget. The sleepy sheep run was quickly turned into a bustling gold town.

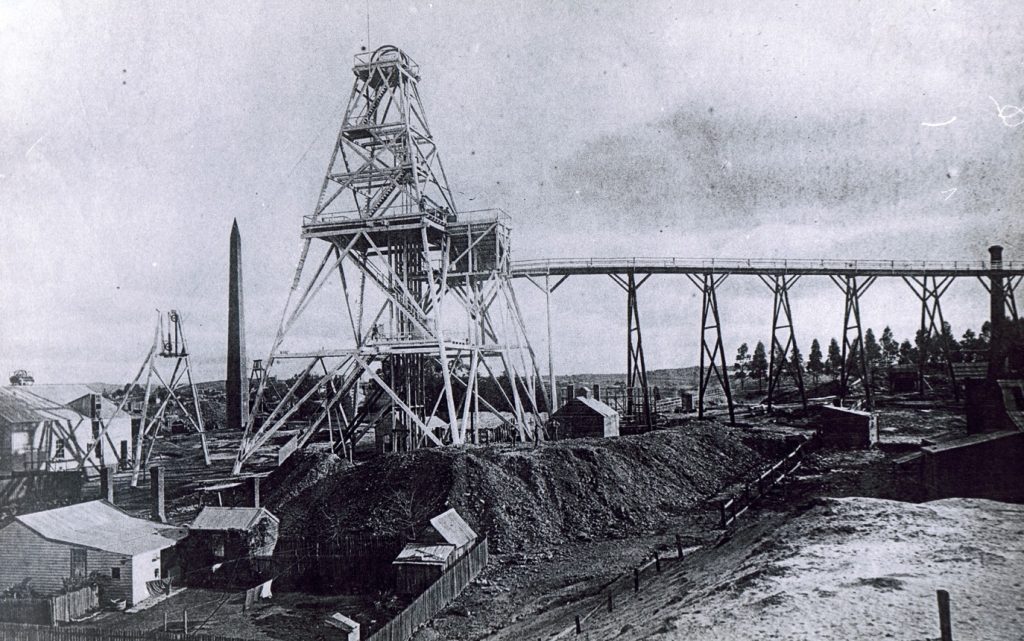

The Mine was opened in 1939 by the Central Deborah Gold Mining Company during the 1930s revival of the gold industry, extending an existing 108ft shaft. At its peak, Central Deborah Gold Mine reached a depth of 412 metres. It had 17 separate levels and 15 kilometres of drives and cross cuts (tunnels).

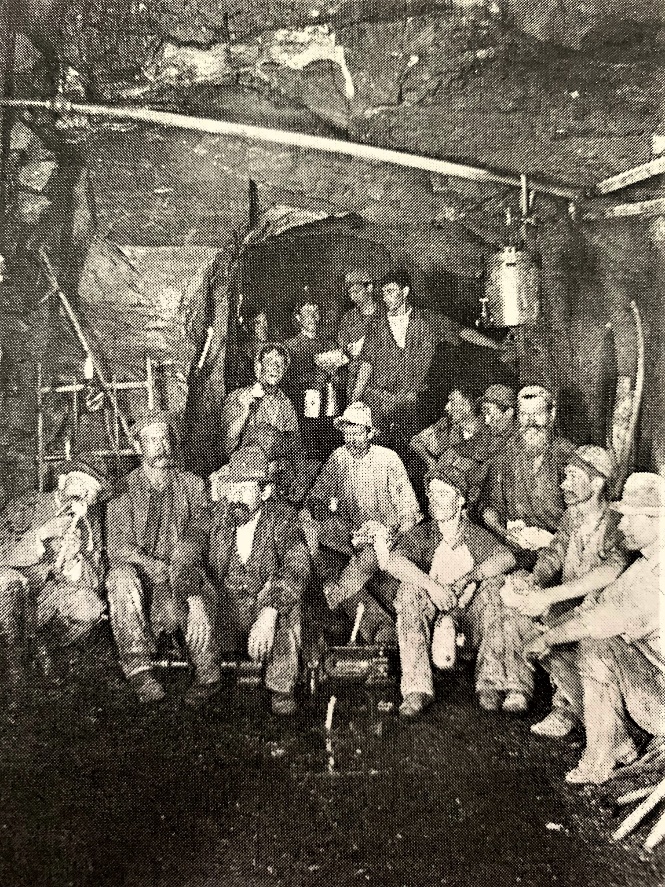

The Central Deborah was very much a hands-on mine and the conditions that the miners worked in would be considered shocking by today’s standards – being lowered underground in a cage with only two sides, often working ankle deep in water, filling 32 ore trucks a shift by hand which were then pushed a mile or more along rails in the drives, working by carbide lamp, breathing in the fumes and rock dust with bells as the only form of communication.

The mine closed when labour was more expensive than what was being removed from below. Once the gold rush concluded the Bendigo skyline changed dramatically with the destruction of the stark mine structures, poppet heads, engine rooms, service quarters, battery houses and chimneys. After intense lobbying by the local community, the Bendigo City Council purchased the still very intact Central Deborah Gold Mine in 1970 to ensure that a link to Bendigo’s golden past was preserved. The surface of the mine was opened to the public in 1971 and has attracted many thousands of visitors since, including H.R.H Prince Charles.

So this painting had come to life, its image a major tourist attraction, and yes the Historical Society would be delighted to have the painting.

I was greeted like a VIP and after the photographs and official handing over of the painting I was told I was being taken underground on a tour. The guide was a hoot, incredibly knowledgeable and totally looked the part, though perhaps broader in the girth than the average miner.

The first descent in a cage was loud and crunchy and yep not a place for anyone who

a. disliked closed spaces and

b. deep dark underground places.

Fortunately, those were not among my anxiety triggers. Kitted up with a hardhat, headlight, belt with battery we descended along the corridors through tunnels, including the slightly waterlogged ones. By the time I returned to the surface I had decided to continue a profession as a historian, but heck what an adventure, and all because I found a painting of a mine shaft no one else could see the value in.