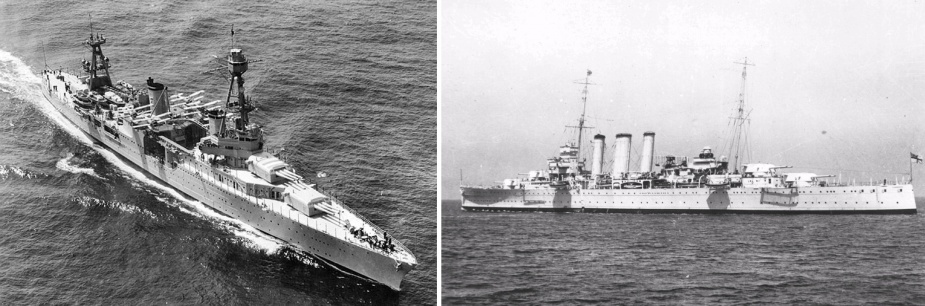

On the evening of 31 May 1942 allied warships flying the flags of several nations moved gently at their moorings in Sydney Harbour. HMAS Canberra was nestled off Farm Cove close to the iconic bridge. From Canberra’s decks the US heavy cruiser Chicago was visible in the dim light, so too the USN ships Perkins and Dobbin. Spread out across the harbour were other HMA Ships: the minelayer Bungaree, the armed merchant ships Westralia and Kanimbla,minesweepers Whyalla and Geelong, the old cruiser Adelaide, as well as the Indian corvette HMIS Bombay. The Dutch submarine K9 was moored next to the ex-Sydney ferry which had been converted to accommodate RAN sailors, HMAS Kuttabul.

It was comforting for Sydneysiders to see such a defended harbour, as these were nervous times. By May 1942 Australians were fighting battles around the globe. They were particularly anxious about a Japanese invasion. Underestimated by the Allies, Japanese forces had pushed with alarming speed through Asia. The impregnable’ Singapore fortress had been captured. The northern parts of Australia and the city of Darwin had been bombed. Even the most optimistic could believe this war was going well. It seemed nothing could stop them.

Suddenly the calm changed abruptly. The blast was loud, and windows shattered. Shore residents rushed outside and looked skywards, it had to have been an air raid. No aircraft was in sight, and then their eyes fell to the harbour waters and a light show the type of which they had never witnessed. Ships, boats of all sizes were moving, the water was ablaze with searchlights and the noise of ships’ piping instructions to their crews, and cranking guns, was deafening. Residents struggled to make sense of the cacophony.

At dusk on 29 May 1942 five large Japanese ‘I’ class submarines had rendezvoused 35 miles (56k) north of Sydney. In the pre-dawn light of the following morning submarine I21 launched a single floatplane which flew a daring reconnaissance mission over the harbour circling Chicago twice before flying away eastwards. The duty Royal Australian Navy (RAN) officer at Garden Island travelled to Chicago to query the origin of the aircraft. He was told that it was an American cruiser aircraft. Though it was agreed there was no other US cruiser in the region no further action was taken.

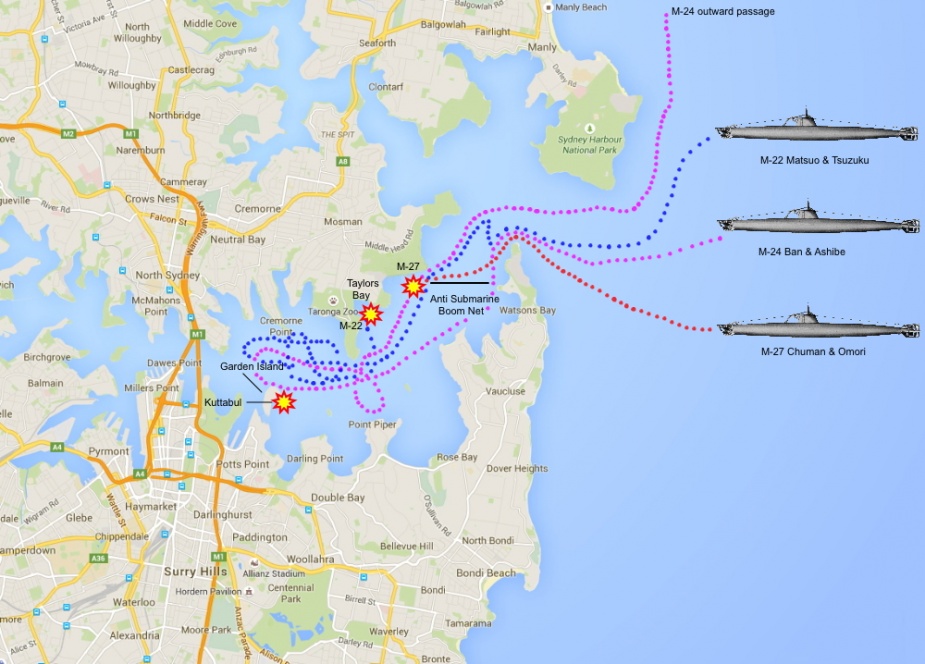

About 9 miles (15k) east of Sydney Heads the Japanese submarines, I27, I22 and I24 released three two crew ‘Type A’ midget submarines. Each was a 24-metre battery-powered submarine, capable of 19 knots submerged carrying two Type 97 torpedoes.

Defence authorities had their eyes firmly fixed northwards and Sydney was defended by only a few coastal guns and anti-aircraft batteries on Sydney Heads. A small flotilla of converted pleasure craft patrolled the harbour, but their nickname was the ‘Hollywood Fleet’ which suggested a less than defence professional ability.

There were underwater electronic cables near the harbour entrance, anti-submarine boom nets, to detect submerged and surface vessels. But only the central section had been completed and the outer loops were too large to detect a midget submarine. At 8pm on the evening of 31 May the first of the submarines, M27, commanded by Lieutenant Chuma Kenshi, entered the harbour. It could have passed on the outer perimeters of the anti-submarine net undetected but unfortunately for the Japanese crew it attempted to progress through the completed centre and its propellers became entangled.

This may have surprised Kenshi but not as much as it did 52-year-old Maritime Service Board employee, James Cargill. An agitated Cargill thought he saw a large shark close enough to the surface for him to use an oar to prod it – it made a metallic sound. He immediately reported the object to Sub-Lieutenant Harold Charles Eyers captain of the channel patrol boat Yarroma. It was a Sunday evening; things were slow and perhaps Eyers thought Cargill had been enjoying a beer or four. He failed to take the message seriously. By 1947 Eyers had only been promoted to Lieutenant. Even this was surprising because the Naval Officer in charge of Sydney, Rear Admiral Gerald Charles Muirhead-Gould later referred to this failure as ‘deplorable and inexplicable’.

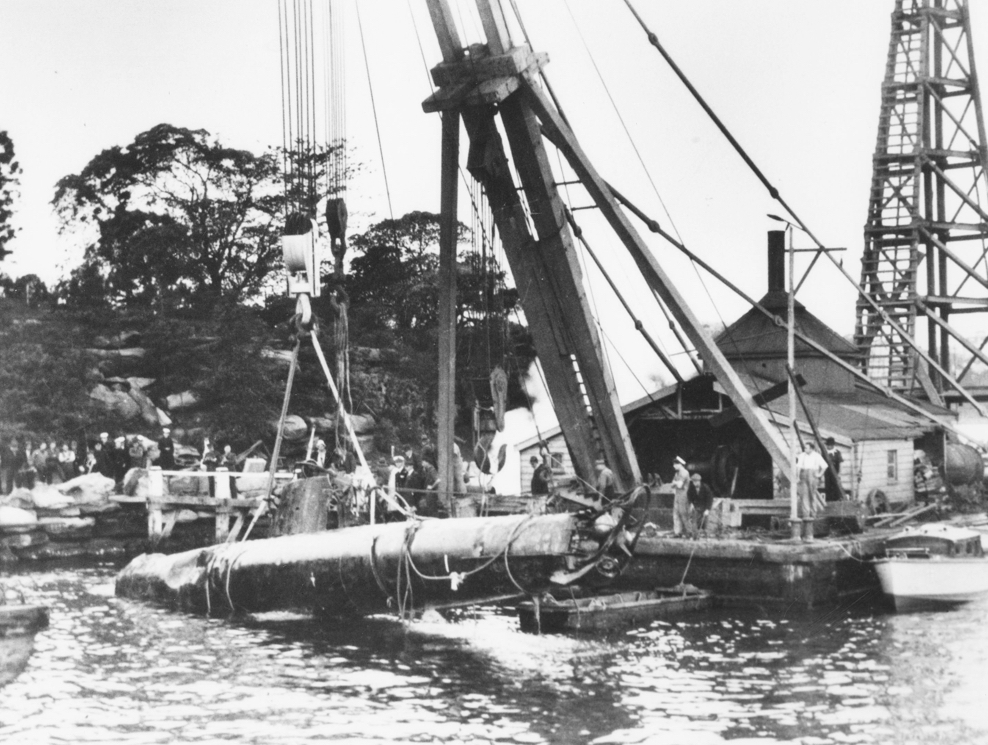

Cargill annoyed that he had not been taken seriously reported higher up the chain of command. He and another Maritime Services employee were sent to further investigate along with another channel patrol boat. The hapless Lieutenant Chuma Kenshi, and his crewman Petty Officer Omori Takeshi continued to attempt to drag their submarine free from the boom net. They finally decided to blow their submarine and themselves up.

The second midget submarine, M24, commanded by Sub Lieutenant Katsuhisa Ban had successfully entered the harbour at 2148. Being moored furthest from the harbour entrance HMAS Canberra duty personnel remained unaware of the imminent danger. Chicago lookouts sighted the submarine’s periscope. Searchlights were illuminated and shots were fired but with guns unable to be depressed low enough this was ineffective. Ban had skilfully positioned his submarine in a perfect firing position against Chicago. His seamanship was excellent, but the midget submarine was extremely difficult to steer. M24 discharged the first torpedo. The submarine bow reared up. Retrimming took time and he may have been temporarily blinded by the Garden Island lights in front of which Chicago was silhouetted.

One torpedo ran ashore at Garden Island but failed to explode. The second torpedo passed under Dutch submarine K9, struck a sea wall, and exploded on impact beneath Kuttabul.

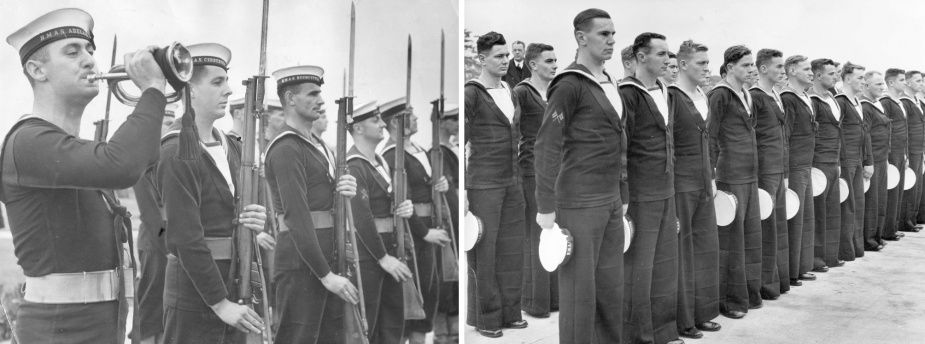

The blast damaged K9 but the RAN accommodation ship sank immediately killing 19 Australian and two British sailors; 10 others were injured, some trapped in the wreckage. West Australian Bandsman Melville Neilson Cumming (20501) had been enjoying some leave from Australia and had just returned from an enjoyable day ashore when Kuttabul exploded and disintegrated around him. Sustaining only cuts he hurriedly removed his boots and dived into the black bitterly cold harbour frantically searching the shattered hull for survivors. Again and again he submerged, and, rescued three injured men. The M24 crew retreated from the harbour. The wreckage of their submarine was not found until 2006 off a northern Sydney beach.

Pandemonium reigned as shrill warship alarms pierced the night. Warships slipped their moorings and moved out of the harbour as quickly as they could. Smaller ships zigzagged harbour waters with an unprecedented urgency. The heavy cruisers Canberra and Chicago were the most desirable enemy targets but Canberra was only manned by a skeleton crew with two-thirds of the ship’s company on night leave. All that could be done for Canberra was to raise enough steam to slowly swing the warship so that it was not silhouetted against city lights – and pray.

Canberra Supply Assistant Russell Keats was spending the night at the Mosman home of a shipmate. They were woken by the sound of gunfire. Realising it was the guns of Chicago they quickly prepared to return to their own cruiser. Whilst awaiting their train Keats ‘lit three cigarettes, considered a harbinger of bad luck’. Canberra’s Engineering Officer,Commander McMahon was enjoying one of his rare overnight stays with his family on Sydney’s north shore. His 12-year-old son John remembers being woken by a hammering on the front door of his home. A policeman spoke solemnly to his father who dressed hastily and disappeared into the darkened city. By the time McMahon was onboard Canberra, harbour defence craft were undertaking a full-scale hunt.

The third submarine M22 with Lieutenant Matsuo Keiu and Petty Officer Tsuzuka Masao within also slipped through the boom net and headed towards HMAS Canberra. By this time the alarm had been raised. Keiu dived. M22 hid on the bottom of the harbour. It was finally sighted in Taylors Bay at 5am by HMAS Sea Mist. The commanding officer, Lieutenant Reginald Andrew referred to the discovery as ‘a shattering experience which caught me very much off guard’. He admitted he was ill-prepared to deal with the situation. The ‘Hollywood Fleet’ quickly earned its nickname when HMAS Steady Hour attacked, dropping depth charges. The charges were unfortunately set for just 15 metres and the resulting explosion lifted Sea Mist out of the water. The damaged craft needed to limp back to dock. As the small craft fleet continued to attack, the midget submarine, now damaged rose to the surface. The crew had shot themselves.

On the morning of 8 June two of the large Japanese submarines fired shells at Sydney and Newcastle. Little damage was caused and Australians on the eastern seaboard began to build air raid shelters. The Japanese never returned. The operation was intended to divert Allied naval power from the Pacific. The ruse was unsuccessful and ultimately the Japanese fleet would be defeated in the Battle of Midway but not before they proved triumphant in the Battle of Savo Island.

Canberra had been fortunate that night in Sydney Harbour. The following day, 1 June 1942, Canberra sailed from Sydney as part of ‘Task Force 44’. The cruiser would never return, sunk in the Battle of Savo Island on 9 August 1942 with the loss of 84, including Supply Assistant Russell Keats, who had lit three cigarettes, the night Japanese submarines terrorised Sydney.

Sydney was in a turmoil. Suddenly harbourside homes were suddenly reduced in value. Australians were disturbed by how close to their largest city the enemy had advanced. The bodies of four Japanese crewmen were recovered, cremated with full military honours and their ashes returned to Japan.

This caused dissent amongst the city’s citizens but Rear Admiral Gerard Charles Muirhead-Gould, DSC, RN, Flag Officer-in-Charge Sydney believed it was honourable and perhaps believed it would indicate to the Japanese that combatants could retain civility to those who fell into the hands of the other side. Unfortunately, the Japanese were not listening.