If you key the words, ‘Women Pirates’ into the web you will immediately be shown skimpy, supposedly sexy outfits that one can purchase to indulge your own or another’s fantasy. Trying to find the truth in an expunged history takes a little more digging. Maritime histories have traditionally portrayed the oceans as a male domain. Swaggering pirates and captains mythologised included Blackbeard, Calico Jack, Captain Hook or the fictious Jack Sparrow, in Pirates of the Caribbean. The popular depiction of the women tend to be victims, either romanticised or semi-pornographic, and it would seem, according to the web, still are. There is nonetheless a rich history of ferocious women warriors at sea, who would rather cut a few throats than submit to this stereotype.

Artemisia

Artemisia, Queen of Halikarnassos, is the first recorded woman pirate, although it may be more correct to call her a naval leader, captaining a fighting ship in 490 BC. Artemisia’s experiences at sea are described in only one record, the story of her fight against the Greeks in the Battle of Salamis, a key battle in the Persian Wars.

Although the Greeks army had been defeated, they still had a navy of 380 vessels from small craft to 125-foot-long galleys propelled by two or three banks of oars; 60 rowers propelling the vessel to around 8 to 9 knots. The Persians knew this force must be beaten and prepared for a naval engagement. The Persians had ships from several nations including that of Queen Artemisia, who contributed five and commanded her own flagship. She was a veteran commander who counselled the Persian King that he should not send his fleet into the narrows lest it be a trap. The Persian King ignored the advice of a mere woman and at the Battle of Salamis the Persian navy suffered heavy losses. Artemisia had hung back and when it was obvious the battle and the Persian navy had lost all semblance of order. Artemisia decided to withdraw and fight another day. Finding herself blocked from the open seas she ordered her flagship full speed ahead and rammed the opposing ship midships. It sank with all hands and her fleet of five escaped. The Persian King was forced to remark; My men have turned into women and my women into men. The Greeks were so infuriated at the success of Artemisia that they offered a large reward for anyone taking her alive.

Alwilda

The Vikings were fearsome seafarers, their longships with sweeping bows decorated with snarling figureheads could carry ten tons of loot back to Scandinavia to be ceremoniously dumped at the feet of the king. Viking women warriors were feared by anyone who got in their way. Alwilda was the daughter of a 5th century Scandinavian King who arranged her marriage to Alf, the crown prince of Denmark. Alwilda refused and with some woman friends dressed like sailors and commandeered a ship. They came across a pirate ship whose crew had lost their captain. The pirates elected Awilda as their Captain and they became successful raiders. The story goes that in time the Crown Prince of Denmark won the day. During a battle with Alwilda and her crew, she was impressed with his fighting ability, agreed to marry him, and became the Queen of Denmark. During the Swedish war there were woman captains named Hetha, Wisna, and Tummi, all referred to as: Captains who had the bodies of women, bestowed with the souls of men.

Grace O’Malley

The Pirate Queen of Ireland was Grace O’Malley. The O’Malleys, like the Vikings, were legendary seafarers, locally referred to as the sea gods of the western ocean. Born in 1530, Grace was the daughter of Black Oak O’Malley, a mighty chieftain who owned a great herring fleet. When he died, she took over her father’s ships, converted them to galleys with 200 fighting men and launched herself on a career of piracy. He was said: She had strongholds on her headlands and brave galleys on the sea and no warlike chief or Viking E’re had bolder heart than she. Grace was recognised as fierce in action and visage. Within a remarkably short time Grace O’Malley established a reputation as a resolute and reckless admiral.

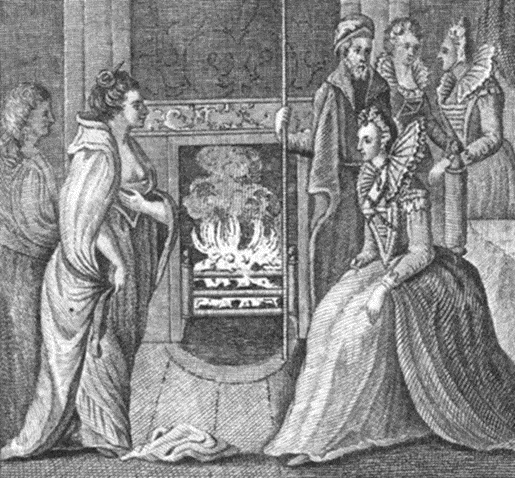

Over the next 50 years she built up her fleet and traded and pirated from Scotland to Spain and led rebellions against English administrators. She even attacked her own son when he sided with the enemy and taught her youngest son the art of battle so well that he fought at Gaelic Ireland’s final stand at the Battle of Kinsale in 1601. This was the time of Tudor England and seafaring was not for the fainthearted. Grace demonstrated great ability in navigating dangerous coastlines, a sound judgement of the elements, and engineered remarkable capabilities in her ships. Her achievements rivalled those of Francis Drake and Walter Raleigh, but history was written by men and the name of Grace O’Malley was not awarded any esteem. Nonetheless, as hostilities between England and Spain escalated English ships attacked others, including the Irish. Grace was at this stage 53. Her eldest son was killed and her youngest imprisoned. Instead of submitting further to English pressure she wrote to Queen Elizabeth I, woman pirate to pirate Queen, requesting her son’s release and a pension for herself. In return she would attack the Queen’s enemies. Elizabeth was impressed with this woman’s reputation and resolve. Her ministers declared Grace to be:

“A woman who overstepped the part of womanhood … the great spoiler and chief commander and director of thieves and murders at sea.”

Elizabeth was curious about this woman pirate who had consistently embarrassed England’s best captains. They were both the same age, and each had broken male expectations. In July 1593 Grace sailed her ship to Greenwich and had a cordial audience with the Queen. Grace’s son was released and the English dignitary who had once captured and jailed Grace was banished. Both Grace and Elizabeth, so different yet so similar, died in 1603.

Laskarina Bouboulina

While Grace O’Malley was eventually restored to maritime history it took longer for many others, like Admiral Laskarina Bouboulina. According to the guidebooks from the Greek Island of Spetsai, Laskarina lived 1771-1825 and was:

While Grace O’Malley was eventually restored to maritime history it took longer for many others, like Admiral Laskarina Bouboulina. According to the guidebooks from the Greek Island of Spetsai, Laskarina lived 1771-1825 and was:

“Not only a pirate but a sea warrior whose name was synonymous with courage and heroism.”

Like Artemisia and O’Malley, she was a mother, (of six children and three stepchildren). She too learnt her seafaring skills from her father and, two husbands both killed by pirates. Commanding eight ships from her flagship Agamemnon (the largest corvette in the Greek fleet) Laskarina proved herself the heroine of the Greek War of Independence against the Ottomon Empire of 1821.

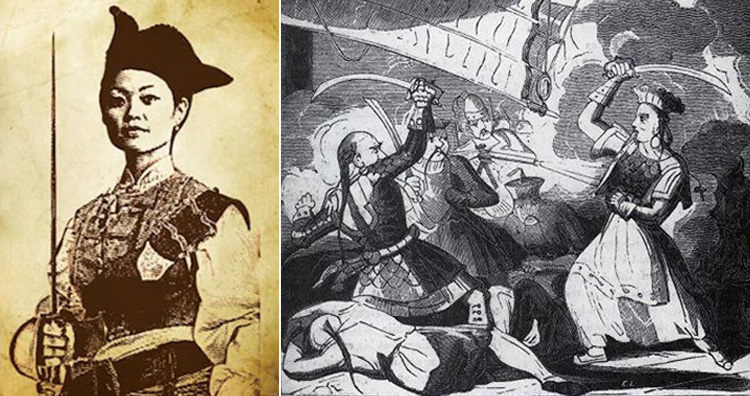

Ching Shih

Another who slipped through the history annuals, likely because she like Laskarina, was not Anglo born, was Ching Shih, also known as Zheng Yi Sao. Born into humble origins in 1801 she married the pirate Cheng I. Piracy in China, as in the West was one of the oldest professions and the husband and wife created a feared confederation of 400 junks with 5,000 pirates. The fleet terrorized the South China Sea but the death of her husband in a gale in 1807 caused Ching to fight for control of the fleet. She achieved this by introducing a formal power structure and elaborate scheme for the sharing of booty. Of course, Ching ensured it was she who controlled the combined financial operation. She then developed a protection racket offering ships safe passage along the coast. By 1808 her organisation was more powerful than the provincial navy and Ching forced political and international diplomatic resolutions. By 1810 she had tired of her life at sea and after negotiating with Chinese authorities that her pirates be allowed a peaceful life ashore, she kept an infamous gambling house until her death in Canton in 1844, aged 69.

Anne Bonney (left) and Mary Read (right) circa 1724.

There were many women pirates and warriors, but their stories were largely suffocated in the early nineteenth century by the new bourgeois conservative idea of womanhood. Women like Anne Bonnie and Mary Read, Mary Lacey, Mary Ann Arnold and Hannah Snell spent time disguised as men before they proved themselves in battle, revealed themselves as women and were then accepted as members of the crew. They were young widows left with no means of support or simply yearned for the same adventure and life on the sea sought by their brothers. Mary Ann Talbot was wounded in battle on the British ship Brunswick in 1794. Assigned to another ship which was captured by the French, she was imprisoned. Although later freed she died in 1808 aged just 30. Hannah Snell grew up in a working-class family of nine children. She ran away to sea in search of the man who had abandoned her pregnant. The baby did not survive so she signed on as ‘James Gray’ on the man-of-war, Swallow. She became a skilled sailor and was wounded in battle. When teased for her inability to grow a beard she would challenge any member of the crew to beat her at any shipboard task.

Hannah Snell

In 1750 Hannah purchased a pub, married twice, gave birth to a son, but in 1789 she was declared insane and died in a mental hospital three years later. Perhaps she had challenged society too many times.

Women pirates, pirate queens and other seafaring women, disprove academic history and the dominant nineteenth century theories surrounding women’s abilities, strength and stamina. Because they challenged, the favoured feminine stereotype, their exploits and significant achievements were largely ignored.