Published in Wings Magazine

THE PRICE OF BEING A HERO

Only once did he end up in the frigid English Channel awaiting rescue.

It is not known why his war service in England only came to 10 months. His promotion was rapid — a Pilot Officer in February 1941 and Acting Squadron Leader seven months later. Regardless that they were celebrated Spitfire pilots, British authorities were slow to promote Australians.

A bar was awarded to Truscott’s Distinguished Flying Cross in October 1941, the day after he sailed for Australia.

His next duty posting was RAAF 76 Squadron flying Kittyhawk aircraft. It was 22 June 1942 when he took to the air in a Kittyhawk and made no secret of the fact that he preferred the Spitfire. On 6 July 1942, the Commanding Officer of No. 76 Squadron, Squadron Leader Peter Turnbull DFC, himself a renowned fighter ace, wrote to his superiors. His squadron was about to move to a forward New Guinea battle area and all was not well.

“Every step is being taken to remove misfits of personnel in this squadron,” he wrote. “It is respectfully submitted that a source of discontent is shown in the unorthodox appointment of F/O (A/S/Ldr) K. Truscott. This junior officer for whom there is nothing but praise (but who is neither more or less worthy of that praise than any other of the 30 pilots of this squadron) finds himself in a most invidious position.”

THE HANDWRITING WAS EXEMPLARY and profuse.

Keith “Bluey” William Truscott wanted to join the RAAF as an aircrew trainee on 21 July 1940. Selection was extremely competitive, so the 23-year-old figured he needed to add as much detail as possible. He came from a well-to-do South Yarra family, could answer the question “yes”, he was “of pure European descent”; he had attended a prestigious private Melbourne school and was in the white-collar profession of “clerk”. His character references from his school were glowing, citing his excellency as a sportsman, particularly AFL, his “frank personality and his capacity for leadership”.

Truscott hoped that resigning from teacher training would not count against him, nor the fact that he had no engineering or flight training, as some other candidates had. In truth, little would have denied him RAAF aircrew entry. The recruiters were already impressed — if not a little star-struck. Truscott was an accomplished footballer, a popular sporting personality of the 1939 Melbourne Football Club’s premiership team where thousands had cheered as he kicked goals.

His entry was expedited in record time and he was accorded immediate trainee pilot status on 22 July 1940. By November, he was in Canada, part of the Empire Training Scheme.

He unsurprisingly wanted to be a fighter pilot; most aircrew applicants wanted to be fighter pilots. Truscott was quickly granted that mustering. The early reports on his flying ability were nonetheless far from glowing. The biography appearing on the Australian War Memorial website includes:

“He was not a natural pilot and almost failed his course. His position as something of a public figure afforded Truscott a chance to continue flying, and he eventually earned his wings despite becoming known for his poor landings.”

His first report was marked “below average”. In August, his instructor wrote that Truscott was a “very good type” and demonstrated “plenty of fight”. The reports regarding his flying ability were not complimentary:

• “Average. Tendency to roughness.”

• “Rather unsteady generally.”

• “Judgement of height during landings very poor.”

• “Progress unsatisfactory.”

But improvement would come with practice. In February 1941, Truscott was awarded his flying badge.

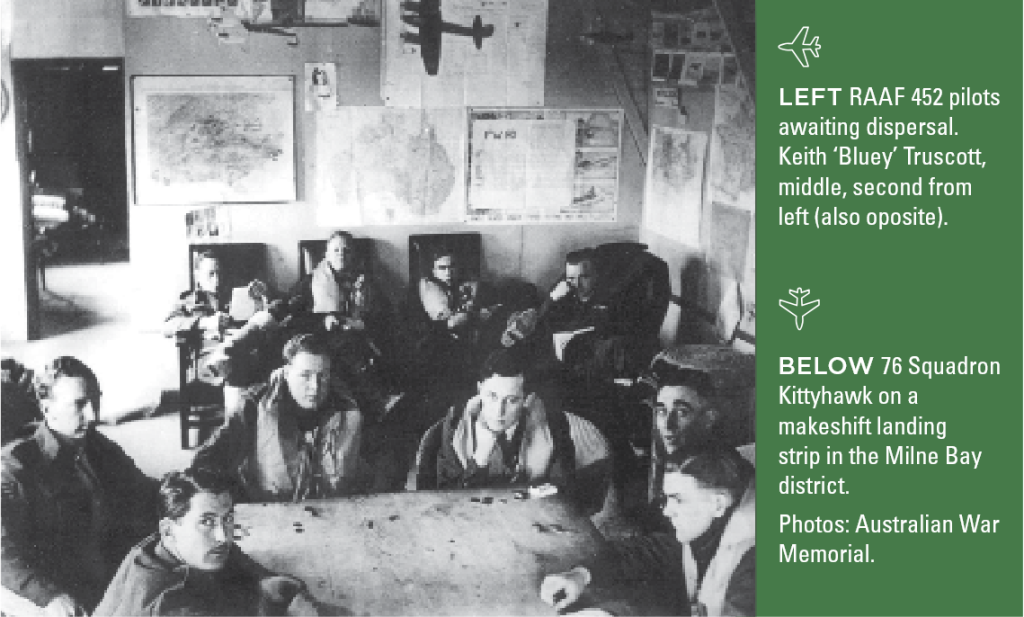

He disembarked in the United Kingdom at the beginning of March 1941 and was serving with RAAF 452 Squadron within a month. His first flight in the Spitfire was 7 May 1941 and his last operation was 16 March 1942.

During this time, he destroyed 11 enemy aircraft and likely three more while on convoy escorts and attacks on German shipping and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Truscott was being paid squadron leader rates — twice the rate of the other pilots — which was “unfair” to all concerned. He hoped authorities would reconsider before his squadron “goes into battle”.

The Commanding Officer of RAAF Townsville supported Turnbull, writing an equally strongly worded letter to RAAF Headquarters Northeastern Area on 8 July 1942. He was concerned with disquiet within 76 Squadron. He accentuated the fact that “teamwork, smooth running, close co-operation of all concerned, especially the pilots, is essential.”

He took issue with the demotion of accomplished pilots returning from England who were now serving in a unit where “the unorthodox appointment of F/O (Acting Squadron Leader) K. Truscott” had occurred. It was a struggle to understand this, and the lack of “consideration given to the feeling of A/Sqdn Ldr Truscott, who has found himself placed in this invidious position.”

On receipt of the letter, a Headquarters authority underlined “no consideration” and wrote in the column:

“Ask the politicians!!”

On 19 July 1942, Truscott was involved in a Kittyhawk accident. He was slightly injured but cleared of blame and no disciplinary action was taken.

Between 26 August 1942 and 5 September 1942, 76 Squadron flew 110 courageous operations, attacking the enemy in the region of Milne Bay, despite unfinished landing strips, adverse weather and heavy enemy engagements.

The Commanding Officer, Squadron Leader Peter Turnbull, was searching for Japanese tanks and while diving on an enemy target, his Kittyhawk flipped on its back and crashed into the jungle. Ground fire was considered a likely explanation. His death was confirmed on 5 September, and Truscott assumed command of 76 Squadron.

Having repelled the attack on Milne Bay, the squadron moved to Darwin and then Western Australia. As of 31 December 1942, Truscott had completed 760 flying hours and was mentioned in despatches.

In Darwin, he was involved in his second Kittyhawk accident but was uninjured.

One night in January 1943, Truscott intercepted three bombers head-on over Darwin and, with just one gun operating effectively, shot down a Japanese bomber.

Towards sunset on 28 March 1943, Truscott was returning to his northern Western Australian base with another Kittyhawk. Over Exmouth Gulf, he spied a Catalina and decided they should undertake a practice attack.

But the Catalina had already lowered its wing pontoons, indicating it was about to land.

The practice attack was not sensible given how low the Catalina was.

The first pilot dropped his Kittyhawk but found the mirror-like surface and false horizon — compounded by bright sunlight in his eyes — alarming, and he hit the ocean surface before recovering.

Truscott should have noticed this and pulled out, but he proceeded.

His Kittyhawk hit the water heavily, the impact tearing off the airscrew, part of a wing and other parts. The aircraft bounced up into the air and caught fire.

The official report stated:

“The attacking aircraft were too low to successfully complete the attack and recover safely.”

An early report haunted:

“Judgement of height very poor.”

A search recovered the body and it was flown to Perth for burial. His parents were given priority air travel from Melbourne and his funeral, with full military honours and dignitaries attending, took place on 1 April 1943.

Political intervention was apparent — and had been throughout the career of Keith “Bluey” Truscott. The government needed heroes for the war effort, for recruiting purposes and Truscott, AFL star and fighter pilot, was popular fodder for the media.

He proved his bravery and commitment, but was dealt unwarranted pressure.

The people of Melbourne mourned the loss of a favourite son.

Dr Kathryn Spurling

Navy veteran. Author of 12 books.

Former guest lecturer in history at UNSW ADFA.