It was 2000 and I received an assignment from the Department of Veterans Affairs, to write a ‘brief for the Queen’. It certainly would be a good addition to the CV, if indeed I was allowed to cite it as such (alas I wasn’t). The assignment nonetheless sounded absorbing.

I was tasked to research and write about ‘trees’, ‘bottleneck trees.’ An unusual project for a military historian? Only when I discovered for whom the bottleneck trees were planted did it not only make sense but proved fascinating. Being a Queenslander I at least knew where Roma was, though it is not the easiest town to visit, being 478.7 km, or roughly 5 hours 25 minutes via the Warrego Highway and A2, from Brisbane.

The rural sector had long dominated the district and attracted men from all over the nation. Before World War 1 agriculture was labour intensive and attracted restless boys who preferred the wide-open spaces. It was these rural men who were the first to flood military recruiting offices and given their horsemanship, the first to don khaki uniform.

The young men living in the Roma distract took little convincing to join up. Not only did it appeal to their adventuresome spirit and the wish to prove themselves men, but the opportunity to travel overseas was something they could never have envisaged without a war. The combat encounter would just be another escape from their monotonous lives.

The consequences from this war devastated the Roma community, as it did so many others, a generation of men wiped from the earth and sad family legacies. It was the legacy which led to the people of Roma and Bungil Shire, to gather on Wyndham Street on 20 September 1918 to plant the first memorial bottletrees in ‘Heroes Avenue’. The Mayor, Alderman Miscamble, explained that since the start of the war in 1914 some 1200 men from the Roma region had enlisted to fight ‘the enemies of the Empire’ and already some 76 had been killed.

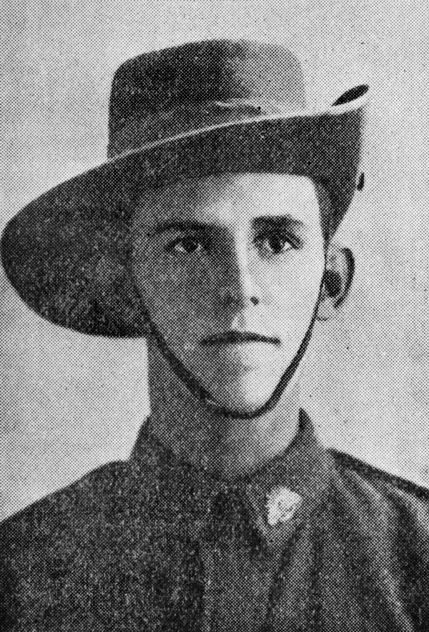

The first tree planted known as Roma’s ‘Tree of Knowledge’ was planted outside the Post Office in honour of Corporal Norman Saunders. He had enlisted on 21 July 1915 and was killed in France on 12 October 1916, aged 19.

They quickly discovered that 27 bottletrees were never going to be enough and the single street intended needed to encompass more thoroughfares. ‘Heroes Avenue’ grew as more families fell into grief, and as the war raged into another year and another.

Engine driver, Private George Brown (1725), enlisted with mates in the 4th Replacements, 9th Battalion, of Roma, on 22 January 1915. On 25 February he transferred to the 49th Battalion. Acting Lance Corporal Brown was killed in action at Messines on 7 June 1917 aged 21. He had no known grave, so his name was added to the Menin Gate memorial Belgium.

Neighbours could but offer sympathy to Rachael Kirby, what else could you do for a mother who received more than one telegram. Widowed when her boys Henry and William were boys she remarried. They grew into strong station hands. The pride was obvious in the photograph taken before they left for an overseas war.

Left, Private Henry Frederick Beitz. Right. Private William Frederick Beitz

Henry embarked from Sydney with the 2nd Reinforcements onboard SS Hawkes Bay on 20 April 1916. He was wounded in action in France on 4 April 1917 and returned invalided to Australia in October 1919. William embarked with the 41st Battalion from Sydney on board HMAT Demosthenes on 18 May 1916. He died, aged 20, on 4 March 1917 of wounds received in action in France.

The list increased and more trees were planted. Another war, more district men dead, too many, to consider planting more trees. Like most Australians the people of Roma and district wanted to forget the tragedies and get on with life.

In 1985 Rebecca Kupfer decided this simply was not good enough, the trees and the bronze plaques beneath bearing long-forgotten soldiers had gone neglected. She began to canvas individuals, the council, and businesses. No one was immune from the enthusiastic Rebecca. The crusade gathered momentum, yes, these young men should not be forgotten. Rebecca attempted to contact families of those memorialised to ask if they were interested in protecting the trees and replacing the plagues. The support was overwhelming, so too from the community who adopted trees and ‘soldiers’ whose family connections could not be found. The local kindergarten adopted one, so too schools, the medical practice, the supermarket, and other businesses. ‘Heroes Avenue’ was restored as it once was, each tree now bearing a brand-new plague and each sponsor becoming intimate with the history of a soldier of the great war. Each Anzac Day, residents gathered beneath ‘their tree’ and offered a floral tribute to the fallen. They then joined the march as it wound itself around the township and finished at the returned soldiers club. Rebecca had set out to ensure the soldiers were not forgotten and had ended up bringing the entire community together.

In 2000 as I researched her list and archive records, I discovered 24 soldiers, Roma boys, who had slipped into anonymity. The township responded and more bottle trees were planted, biographies learned, and sponsors found. With the visit from the Queen fast approaching they hoped I would not find more. I could not agree more, I was now up to 127 WWI soldiers and looking at photographs of the young who perished, was taking its toll on me also. It was time for a little lightness, so I included in my brief, the name and history of Private Oliver Cromwell. I thought British sovereignty might see the humour in an otherwise very sad account.

Private Oliver Cromwell (504) was older than most Roma boys when he enlisted but he died as viciously, a member of the 7th Australian Machine Company, aged 30, on 4 October 1917 in Flanders Field. There was nothing to bury so he, like Roma’s 21-year-old Private George Brown, had his name etched on the Menin Gate Memorial.

The Queen did not visit Roma, Prince Phillip did. I was closeted in Canberra perhaps because of the ‘Oliver Cromwell’ thing but more likely because of my refusal. As I was finishing the glossy fold-out brochure I received a directive from the then Minister for Defence, whose electoral district just so happened to include Roma. I was to make much of a particular WWI soldier, the family of whom continued to reside in the district and were friends and supporters. On investigation I found the hapless private never left Australia unfortunately dying of illness in Sydney. It seemed even war dead were not immune to political favours. I decided to leave the brief as it was. Strangely I never received another DVA history assignment.