There are paper planes in the foyer dangling on string from above. As the door is opened the rush of winter air makes them flutter and bob playfully. This is fitting because there are children’s names festooned on fuselages, and this mid-west New South Wales school, with links to a small English churchyard, is named in honour of a local bloke named Rawdon Middleton who became an aviator and won a Victoria Cross.

Few Australians could say where the town of Yarrabandai was, not even if the names of towns within a radius of 50kms were provided, like Monomie, Ootha, Warroo, Derriwong, Bedgerebong, Gunningbland, Borambil, Nelungaloo, Kadungle, Brolgan, Bundaburra or Wowingragong. It sounded more like an indigenous conversation particularly as Rawdon Hume Middleton could enunciate them perfectly. If those who had asked where he was from still looked none the wiser, he could say ‘Alloway’ the sheep station near Bogan Gate in the Gilgandra district his father managed which was north of West Wyalong, northwest of Forbes, west of Parkes, east of Condobolin. If they still looked puzzled he could just say, New South Wales. Those tongue-twisting towns Rawdon knew very well – he had traversed them often enough on horseback, as a jackeroo, as a spirited boy and man with a quest for excitement and travel. Perhaps it was in the genes because the middle name he carried was in honour of his great uncle, the explorer, Hamilton Hume. He finished his education at Dubbo High School. He loved the vast open spaces that hugged every horizon of this part of the country, but there was again a war in Europe and like so many of his generation he believed it was his duty to enlist.

He was called Rawdon at home but once in the RAAF from October 1940 he was called Ron. He was delighted when mustered as Aircrew (Pilot) especially flight training was just up the road at Narromine. By March 1941 he was in Canada, by September, the United Kingdom. Towards the end of 1942 he was attached to Royal Air Force (RAF) His English superior noted he was, ‘an earnest, plodding pupil. All he did was thorough, though unspectacular’. The British officer failed to appreciate the adjustment needed, from flying over wide open Australian outback space where the light was strong and visibility forever, to flying above a nation full of villages and cities shrouded in grey mists and snow. It was unsettling to be posted to different RAF Bomber Command squadrons. Another Englishman described Middleton as a pilot who:

Brooded a lot on the German bombing of unprotected cities, and followed a common trait among out-back Australians in being inclined to bouts of melancholy.

On 6 April 1942 he was second pilot to an RAF skipper. The Stirling Bomber crew realised it could be a difficult night because the target was Essen, nicknamed by crews as ‘Happy Valley’ due to the warm welcome they received from German anti-aircraft batteries. Take off at 37 minutes past midnight was routine but that changed as soon as the bomber was over Holland. The Messerschmitt attacked and gunfire ripped into the British aircraft damaging the starboard wing. The pilots struggled to keep their aircraft in the air. As the aircraft finally touched down at a friendly airfield the undercarriage collapsed. Other than racing pulses and what would be a few bruises the crew gave thanks to whatever lucky talisman they carried or deity they believed in.

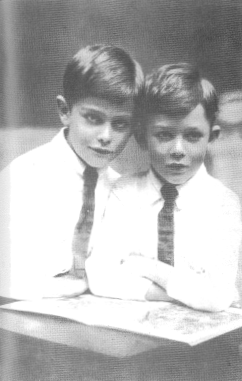

By July 1942 Rawdon was finally allowed to choose his own crew. Quickly the Australian with the Errol Flynn or Tyrone Power looks, assumed a reputation as a first-class aviator and bomber captain. His three RAF gunners elected to continue flying even though they had completed their tour of 30 operations. His wireless operator said Middleton was: ‘About the most modest chap I’ve ever met, and one of the best-looking. He was so efficient’. Middleton enjoyed flying the Stirling because due to the thick wing it could invariably out-turn night fighters. The downside was that the same thick wing resulted in a low ceiling, commonly 12,000 ft (4,000m). Raids on Italy necessitated flying through the Alps rather than over, so not only was there the difficult terrain to master but the aircraft was also an easier target for anti-aircraft fire.

In August the Australian pilot was selected to join the elite Pathfinder Force, he had proved his first RAF superior wrong. The Middleton crew flew as Pathfinders on a raid on Nuremberg lighting up the target for the following bomber stream. On their return Middleton was informed that while he was welcome to be a Pathfinder his crew were not good enough and they would be posted to another squadron. Through loyalty or superstition, Rawdon declined the offer and he and his crew returned to RAF 149 squadron. On the night of 28th/29th November 1942, the attack was on the Fiat works in Turin, Italy. As he released the Stirling’s brakes and jockeyed for position on the runway the 26-year-old was comfortable with his decision. This was his 29th operation, one shy of a completed tour.

The heavily laden bomber strained to climb over the Alps. Visibility was poor and only by squinting could the pilots distinguish the mountain peaks which lurched out of the pitch black. Fuel consumption was excessive and four bombers turned back for England. Flight Sergeant Middleton conferred with his crew and they pressed on. Flak spurted up from below destroying metal, fabric and human bodies. Middleton, his second pilot and the wireless operator were all wounded when a shell splinter burst in the cockpit. Middleton lost consciousness and the bomber plummeted towards the mountainous terrain. His second pilot struggled with the controls and at 800 feet pulled the aircraft out of its deadly descent. House roofs were visible and only when at 1,500 feet again were the bombs released. The Stirling bucked as it was hit over and over again. Middleton was bleeding badly from several wounds and where his right eye had been there was now a gaping bony hole. He took the controls and in a wheezing voice ordered the second pilot back to have his own wounds dressed.

Speaking in little more than a gasp the Australian told those onboard he was determined to get them back to England rather than have them become prisoners of war. He instructed the crew to jettison everything to lighten the load. For four hours the badly wounded Australian flew the bomber, the shattered windscreen exposing him to an icy blast. He realised how serious his injuries were and how unlikely it was that he could bale out. As the badly damaged plane reached the French coast the Stirling was conned by a dozen searchlights, more anti-aircraft fire filled the sky. Middleton could do little to avoid the danger as his aircraft was buffeted by hits to both wings – how it was still flying none of the crew knew and the same could be said for their skipper. The English coast came into sight and never had it looked so welcoming. With only five minutes of fuel remaining and the bomber at 600 feet Middleton ordered the crew to bale out. Believing the bomber could not be landed without endangering civilians below he then pointed the aircraft back out to sea. Two crewmen had refused to go and the last time their aircraft captain spoke was a final order to do so. Their delay was a brave but fatal decision. Their bodies were found the next day, parachutes opened but landing too far from the Kent coast they drowned. The Stirling twisted and bent and out of fuel, finally gave up its struggle and crashed into the sea. Four crew members survived. One reflected:

“No-one will ever know what was going on in Middleton’s mind in those last few moments … During the return home there were many opportunities for us to abandon the aircraft over France, and for Middleton to live. But he preferred that we, his crew, and the aircraft of which he was Captain, should not fall into enemy hands. That was the kind of man he was.”

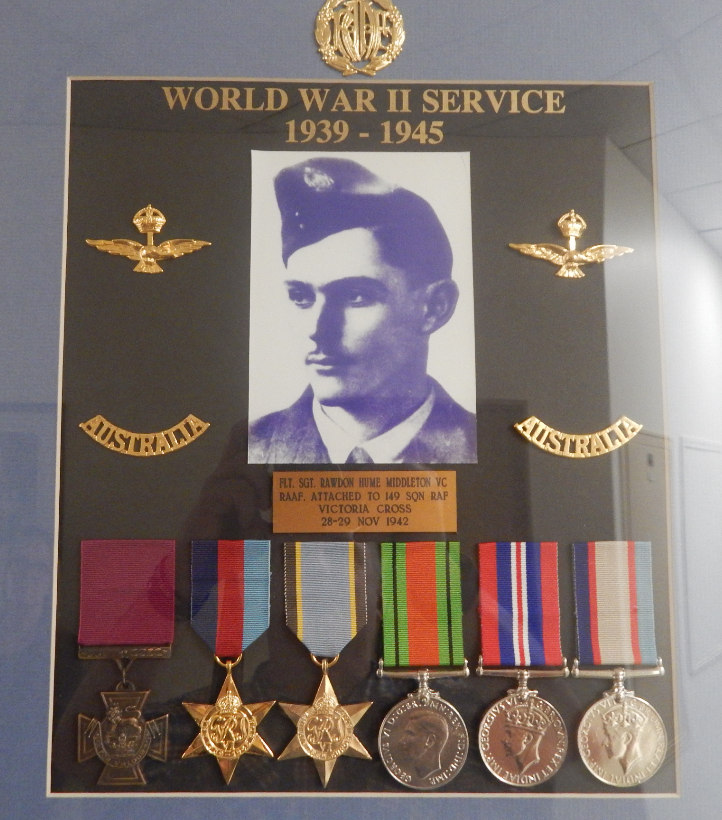

The RAAF pilot from the difficult to pronounce town and district was awarded a Victoria Cross, on 15th January 1943, with the citation: ‘His devotion to duty in the face of overwhelming odds’. The RAAF had its first VC, won by an aviator who had inspired his crew to ‘heroism of a high order’. Rawdon Middleton’s body was not recovered from the ocean until 1st February. He was given a funeral with full military honours.

Unfortunately, Rawdon Middleton was buried in Beck Row (St John) Churchyard, Suffolk, England, landscape very different from the wide brown plains of NSW he loved.

But there is a vibrant living legacy to this outback bloke. Middleton Public School, South Parkes, NSW, was opened in 1957. There is a plane on the crest and the school song includes: ‘We remember Rawdon Middleton, after whom our school is named, a bomber pilot, brave and loyal, until the very end’. In the foyer there are paintings and photographs of Rawdon, a model of a Stirling bomber, medal replicas, and most sobering, is the flag which was draped over his coffin (encased in glass). But there is also the presence of children and their uncomplicated joyful outlook on life. Teachers hand out tokens to students who display respect for others, responsibility, and show enthusiasm in their studies. The tokens are placed in a box from which three are drawn each Friday. These pupils are presented with a certificate of achievement and a coloured band for their wrist. For a week they wear a special badge and, their name is attached to an aircraft dangling amid fluffy white hardboard clouds suspended from the foyer ceiling.

It is sad to drive in search of Middleton’s home now. As with so many country towns the population drifted away, and Yarrabandai is no more. Nearby Trundle also a shadow of its former self, just a shop and the Trundle Hotel which claims the second longest hotel balcony, in the state. With some searching I find an honour board bearing his name, in the War Memorial Hall, a building which reflects much grander times. And above the now never used hall entrance a rare find a dusty painting – Rawdon Middleton.

It is easy to believe that, after the horrors he witnessed in the skies over a Europe at war, Rawdon Middleton would have been pleased to be associated with a place of laughter, learning and young Australians. He likely would be proud that they were rewarded for positive traits and endeavour, and innocuous, paper planes.