On 30 December 1911 the Australian Government advertised for ‘two competent mechanics and aviators’ to be appointed to the Department of Defence. One of the requirements was for the applicants to advise if they were married or single perhaps an indication as to the precarious nature of future employment, as was the clearer giveaway: The Commonwealth will accept no liability for accidents. This was the first official foray Australia took into a future which would be dominated within decades by aviation and air warfare.

Unsurprisingly for the period, Australian bureaucracy chose an English gentleman, Henry Aloysius Petre, descended from the 11th Baron Petre, a solicitor by profession. Nonetheless Petre’s aviation accomplishments made him an easy choice. A hero of earliest aviation, Frenchman, Louis Charles Joseph Blériot, had captured Petre’s imagination. Blériot was an inventor and engineer who through profits from his car headlamp invention and manufacturing business was determined to build successful aircraft and founded Blériot Aéronautique. His combining a hand-operated joystick and foot-operated rudder control system revolutionised aviation, as did his monoplane. In 1909, Blériot became world-famous for piloting the monoplane across the English Channel.

Impressed by Blériot‘s pioneering cross-channel flight Petre gave up his legal practice, borrowed £250, and with design assistance from his architect brother, Edward, proceeded to build his own aeroplane. Although the aircraft crashed on its maiden flight Petre was not discouraged, took flying lessons and obtained his Royal Aero Club Aviator’s Certificate in 1911, before becoming an instructor. He was a man in a hurry and by the following year was a pilot and designer with Handley Page Limited. On Christmas eve 1912, Edward Petre, was killed attempting a flight to Edinburgh. Rocked by the tragedy Henry applied for the position a world away and arrived in Australia in January 1913.

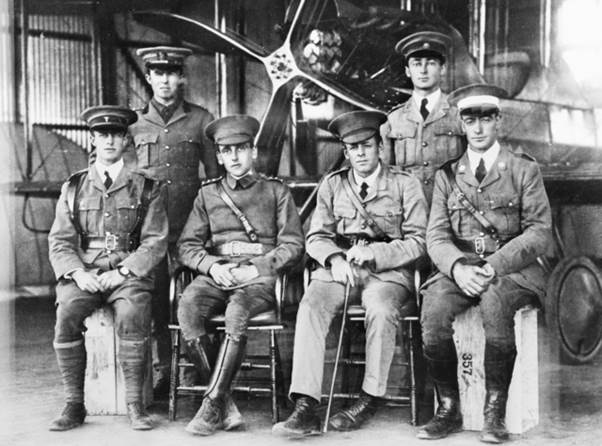

Petre rode his grief thousands of kilometres on a motorcycle through this new broad land seeking the perfect site for a Central Flying School (CFS). He convinced the Australian Government that 295 hectares (730 acres) at Point Cook, Victoria, rather than Canberra’s Duntroon was the ideal place for the base he was to command. Lieutenant Petre was joined by the second aviator choice, Australian, Eric Harrison. Though born in Victoria Harrison had journeyed to Britain to become a pilot and then an instructor. He was delighted to be able to return to the land of his birth, be commissioned Lieutenant, and work with Petre to create the Australian Army’s Central Flying School at Australia’s first military airfield. The Australian Aviation Corps was established with just five flimsy aircraft: two Deperdussin monoplanes, two Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 biplanes, and a Bristol Boxkite, at the beginning of March 1914, and Petre and Harrison began to train pupils in basic aviation.

Flight was a fascination in Australia, something marvelled at but only experienced by a handful of citizens. Regardless there was no shortage of willing candidates eager to test themselves in this exciting adventure. The CFS commencement was not auspicious. On 9 March 1914, Petre registered Australia’s first military flying accident when, trying to avoid telephone wires on landing, he crashed a Deperdussin. The pilot escaped with bruising, but the aircraft was destroyed. Training was elementary conducted over three months in the confines of the aerodrome’s boundaries with aircraft flying at heights of between 15 and 60 metres as long as there was no wind. The first four graduates were: Captain Thomas White; Lieutenant Richard Williams, Lieutenant David Manwell and Lieutenant George Mertz.

Thomas White was born in Melbourne in 1888 and attended Moreland State School. Family circumstances prevented him from accepting a scholarship to Scotch College. He quickly joined the Citizen Military Forces (CMF) as a bugler. Excelling at numerous sports indicated an ambitious, adventurous character and he lost no time in embracing opportunities. By 1911 he was commissioned into the 5th Australian Regiment, by 1914, he ensured he was selected as one of the first to fly. Richard Williams was born at Moonta Mines, South Australia in 1890 and educated at Moonta Public School. Employment as a telegraph messenger and then bank clerk lacked the excitement, he yearned, so at 19 he enlisted in the South Australian Infantry Regiment, Australian Military Forces, was commissioned in 1911 and accepted for the first AFC course in 1914.

David Thomas William Manwell was born in Queenscliff, Victoria, in 1890, and educated at Queen’s College, Maryborough. His civilian occupation was Commission Agent, but his passion lay in being a Lieutenant in the 16th Light Horse from 1912 and convinced authorities he was the right stuff for the nascent AFC. George Pinnock Merz was born at Prahran in 1891. By any interpretation Merz was an overachiever. When studying at the University of Melbourne he was commissioned a second Lieutenant in the Melbourne University Rifles. He graduated medicine in 1914 before becoming dux of the first AFC course. Merz was one of two pilots selected to accompany the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF) to Papua New Guinea at the beginning of the war. On his return he was appointed instructor of the second flying course, while at the same time working as a doctor at Melbourne Hospital.

Following a request from the British Government of India on 8 February 1915, the Australian Government agreed to provide aircrew and ground staff to offer air support for the Indian Army which was attacking the Ottoman Empire in Mesopotamia (now Iraq). Petre quickly volunteered and departed for Bombay on 14 April to be in charge of the Mesopotamian Half Flight. White, Merz and Lieutenant William Harold Treloar, along with 37 ground staff embarked on RMS Morea for India in late May.

Treloar born 1889 was the son of a grocer. Employment as a Stock, Station and Commission agent enabled him to indulge his interest in motor cars, both driving and the mechanics of. Along the way he was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the 70th (Ballarat) Infantry Regiment. In early 1914 he sailed for England to follow his aviation ambitions and by mid-year was a seasoned pilot. On hearing instruction had commenced at Point Cook he rapidly returned, completed a three-week course in aerial observation at the CFS in February 1915 and then a three-week pilot’s course.

When Petre and his men arrived, they found appalling conditions. The airfield was in swampland and the breeding ground for mosquitos meant twice daily quinine tablets were necessary to stave off malaria. The sandstorms which tore canvas tents to pieces just something else to endure. The aircraft were obsolete. The two Maurice-Farman Shorthorn biplanes and single Longhorn aircraft were very unsuitable for desert conditions and capable of only 50 mph (80 km/h). Given the desert wind (shamal) commonly reached 80 mph (129 km/h) the Australians were unimpressed to find themselves invariably flying backwards. Added to this hazard was another, the warm atmospheric conditions ‘about 110 to 120 degrees in the shade’ and oppressive humidity,reduced the lift capability to enable the aircraft to even take off.

This world of military aviation would revolutionize warfare in the decades to come but at the commencement of World War I there were few tactics and much to prove. Senior British army officers had little faith in what they did not or wish not, understand. Members of the Mesopotamian Half Flight were at best seen as a slightly amusing sideshow.

There was comfort in numbers, and they were joined by New Zealander Lieutenant William Burn and two English pilots attached to the Indian Flying Corps, Captains Philip William Lilian Broke-Smith and Hugh Lambert Reilly, as well as nine more mechanics. Operations commenced on 31 May with reconnaissance flights. Enroute, they attempted to drop three 20-pound bombs on a Turkish paddle steamer. They missed but the bombs exploded forward and aft of a smaller craft. The Turkish crew was terrified and promptly surrendered to the first British ship that appeared.

Within months two Caudron G.3 aircraft, though not modern and more suitable for training than action, improved operability and enabled the flight to conduct more reconnaissance flights and to carry despatches between the front and Basra. On 30 July 1915, Lieutenant George Pinnock Merz, the Dux of the first AFC graduating class, and his New Zealand observer, Lieutenant William Burn, flew 160 kms from Basra to support army ground forces in the Battle of Nasiriyeh. On the return leg mechanical failure forced them to land in enemy territory. With only pistols to defend themselves they engaged in a running battle with well-armed Arab tribesmen. Their bodies were never found. Mertz, the Melbourne doctor, was 23, and accorded the unenviable title of being the first Australian military pilot killed in action.

Four Martinsyde single-seat scouts reinforced the unit, now known as 30 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps (RFC), in August. Petre test flew the first and was disappointed that even at the maximum speed of 80kph it took 23 minutes to reach an altitude of 2000 metres – the barest improvement on the Maurice Farman and Caudron.

This first AFC unit to see active service was quickly caught up in as ill-conceived a campaign, as their Australian Imperial Force (AIF) brethren were elsewhere from April 1915. In both, British military hierarchy severely overestimated their own strategic aptitude and underestimated the enemy’s strengths. In this precarious early chapter of war aviation the Australians suffered high casualties, with worst to come.

On 16 September Captain William ‘Harold’ Treloar and his Indian Army observer Captain Basil Atkins were on a reconnaissance flight when the engine died. Treloar managed to guide the Cauldron to the ground. Unfortunately, they were close to Turkish lines. They attempted to run but realized this was impossible. They were taken prisoner and incarcerated in numerous prisoner-of-war camps until Turkey surrendered on 30th October 1918.

The remainder of Half Flight were struggling to stay alive both in the air and on the ground. Captain Thomas White had several close encounters with the enemy. On one photographic reconnaissance flight White and Indian Army observer Captain Francis Yeates-Brown were flying at 1500 metres trying to evade Turkish anti-aircraft fire, when the engine lost power. White opened the trottle and dived steeply. The engine coughed but not with sufficient revolutions to avoid gliding to the ground. Enemy troops were sufficiently surprised for White to continue to taxi the aircraft across the cracked earth while his observer stood with a rifle at the ready. White had dropped bombs on this very column of soldiers and had no wish to fall into their hands. He agreed later that it was pure luck that the two men in their flimsy aircraft bumped along a road for more than 25 kms before whatever the engine obstruction was, cleared, and they became airborne. They returned to their airfield in time for breakfast.

White and Yeates-Brown’s next operation was as exciting but there was no return. They volunteered on 13 November to attempt to destroy telephone lines west of Bagdad. It required them to fly a round trip of 200 kms, over Turkish lines, landing 14 kms from the city between telegraph poles close to a road which was the main enemy thoroughfare. A gust of wind pushed the wing of the landing aircraft against a pole while a column of Turkish horsemen galloped in their direction. With White firing a rifle at the approaching troops, Yeates-Brown successfully set charges and destroyed poles and wires. They were roughly overpowered and taken prisoner.

By December 1915 the Indian Army was defeated. Nine Australian Half Flight ground staff were taken prisoner with only Flight Sergeant J.McK. Sloss and Air Mechanic K.L. Hudson surviving captivity. Petre, the remaining Australian pilot, escaped in the only airworthy aircraft and flew to Egypt on 7 December. He and the eight Australians at Basra joined the newly formed Australian Flying Corps in Egypt early in 1916.

Lieutenant Eric Harrison had taken charge at Point Cook and he and his staff strived to fulfill the demand for pilots for a war which engulfed the world. Like Harrison, several Australians had followed their ambitions to Britain to fly and were now part of British squadrons. As members of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) bled and died in the rock and sand of a Turkish peninsular, flying overhead was Australian Royal Navy Air Service Captain, Arthur Harold Keith Jopp, spotting and bombing Turkish positions.

Dr Kathryn Spurling is a member of the RSL Woden Sub-Branch. She is the author of ten books, her most recent, From Fury to Hell: WWII Australian aircrew prisoners of Germany, will be launched by New Holland in April 2022. This is an extract from the book she is writing about the AFC and Captain William Valentine Herbert. www.kathrynspurling.com