Merle Hare (nee Storrie) is an iconic figure in the ACT naval community. Remarkedly spry, she continues to live independently in the same villa she has called home for 25 years. Merle doesn’t use a stick but suggests she is slowing down. Merle Hare is 105 years of age.

Merle Kelway Storrie grew up in Sassafras, a tiny settlement in the idyllic Dandenong Ranges of Victoria. She had a fraternal twin; her brother was Donald Kelway. Their sister Alva Kelway was 14 months older.

Merle and Donald Storrie (Hare)

With the outbreak of World War II, Donald entered the RAAF in late 1940. Alva joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) in 1941 and on 29 March 1943 Merle enlisted in the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service (WRANS).

Merle had been working in the Myers Emporium Melbourne, salaries office. Donald was training to be a fitter and turner, perhaps with views of becoming an engineer like their Marine Engineer father. Merle continues to speak fondly of those early days. Each week she was driven in a Chevrolet limousine with ‘two large men’ escorting her to hand each Myer employee their pay packet. A large responsibility ‘for a little girl from the country’. She boarded with an aunt and every weekend she and Donald drove home to Sassafras taking fresh food from Victoria Markets for the family. And then Australia was committed to a war in Europe.

Merle had considered following Donald into the Air Force. Her immediate Myer superior convinced her otherwise, arguing that whilst there were already a significant number of women in the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF), the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) was now accepting women for the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service (WRANS) to release men for sea duty. Merle raised herself to her full 4ft 10inches (1.47m) and presented herself to RAN Recruiting, HMAS Lonsdale, Port Melbourne, to enlist as an Assistant Wran Writer on 29 March 1943.

The RAN was totally unprepared for the influx of women. For the first WRANS recruits through Melbourne there were no uniforms, no accommodation and a tiny stipend. By the time Wran 940 Merle Storrie entered there was still a delay. In the interim there was a lot of marching and learning naval jargon.

We marched back and forth along the wharf, sometimes the lack of supervision meant we could have marched right off the wharf.

Merle Storrie (Hare)

Merle continued to live with her aunt. There were still so few Wrans, that their uniforms were individually tailor made.

There were about 100 of us in the first intake and we had to wait until they built our huts at Flinders Naval Depot.

On 21 April 1943 Merle finally posted to Flinders, HMAS Cerberus, the main RAN Training Depot, which clung to the shores Western Port Bay. After her initial training and promotion to Wran Writer on 31 May 1943, Merle was quickly accorded responsibility. Primary duties were in the victualling office costing and ordering food supplies, a big assignment as all personnel preparing for war trained at Cerberus. Merle explained with compassion that the male RAN Chief Petty Officer (CPO) in the office struggled with what we now know as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). His ship had been sunk from beneath him and he was struggling emotionally, causing his frequent absences from duty. Merle and another Wran ‘just needed to get on with it all’.

This did not go unnoticed by the Officer in charge who arrived to complement ‘the terrific young women’. Merle was promoted to Leading Wran Writer on 1st October 1943 before being transferred to Leading Wran Supply Assistant on 30 Oct 1943. Her abilities were sought by two different navy sections and Merle transferred to the Supply Category and section.

The Wrans were accommodated in the ‘Wrannery’ a collection of wooden huts, each holding 24 Wrans in six bed cubicles with a bathroom between. Being so close to the water meant sea mists and chills were just part of the living conditions. They worked hard and long hours. ‘We were always in uniform. The day would start with ‘Wakey Wakey!’ at 0600, breakfast at 0700’. Wrans would then march to their different workstations. At 1900 hours the duty WRANS Officer would inspect each Wran’s bed and kit as they stood at attention. ‘We did our jobs and enjoyed life’. Merle loved the camaraderie. Being away from home and living in barrack style accommodation with women was new for this generation of women as was the close companionship and independence. ‘We lived securely and happily … I loved every minute of my time in the Navy’.

On weekends the residents of the local township of Crib Point, staged a dance for naval and RAAF personnel. Being a Leading Wran, it fell on Merle to march the Wrans from their huts out of the Cerberus gates and to the dance. That was commonly the easy part. Maintaining the formation on the return trip was a little more difficult as liaisons had formed at the dance. Some of the male followers could be dispersed by Cerberus gate sentries, but sailors needed to be told firmly to return to their own quarters once the Wrannery was reached. Merle recalls one night a very new sailor was on sentry duty close to the Wrannery when two Wrans were ‘sneaking around in the dark’ to meet their sailor boyfriends. After shouting ‘Halt who goes there’, he fired his rifle. Those in the Wrannery woke with a fright; no one was injured; but Merle recalls two women were discharged from the WRANS.

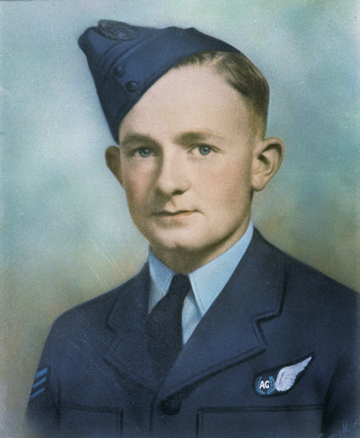

Merle’s twin brother Donald Kelway Storrie was a fitter and after training in numerous RAAF bases, he became an RAAF flight engineer, his secondary duties were as an air gunner. Don served operationally with No. 22 Squadron before joining No. 20 Squadron flying Catalinas. Whilst training at Wagga Wagga he met Alma and the couple married. Merle was to be a bridesmaid, but she needed to battle to be there.

Sergeant Donald Storrie. (Hare)

Merle fronted her superior with her written leave request. It was ripped up in front of her with the retort: ‘Don’t you know there’s a war on?’ Merle was not about to be denied.

I stood to attention in front of her, and I said, ‘Madam, I wouldn’t be here if there wasn’t a war on.’ She didn’t have an answer for that, and I went back, and I told the CPO what had happened. He jumped to his feet … and I got leave to go to my brother’s wedding.

That was the first hurdle overcome but others followed. Travel was stopped for all individuals except for ADF personnel, if they were fortunate. Merle secured her ticket through the RAN but was not allowed on the train. Her brother even suggested she take his seat until Merle reminded him, ‘Don, you can’t get married without you’. She had acquired her ticket at 1100 but moved from queue to queue all day attempting to secure a seat. By 1700 a military official finally noticed and took her into the ticket office. In an assertive tone he told the clerk that ‘this lady has got to get to Wagga Wagga’. A seat captured; Merle was told ‘don’t move for anybody; just stay there’. She was the only family member who managed to attend Don’s wedding, as a bridesmaid, ‘all dressed up in blue’. Little did Merle realise at the time how significant this occasion and her attendance was.

Merle Hare second from left, next to her twin brother Don. (Hare)

Merle was herself engaged to fellow Victorian Robert Richards Hare a gunner in an anti-aircraft battery with the AIF 9th Division. The former salesman had enlisted on 26 June 1941 and who had served at El Alamein, Finschhafen and Lae.

Robert Hare. (Hare)

It wasn’t the original plan. Merle had been keen on Alan Hare pre-war, but their mothers encouraged the relationship between the older brother Robert and Merle. She visited her old workplace, Myers and asked if they could assist with anything she could make into a wedding dress in this time of stringent wartime coupons and shortages. From the storeroom emerged ‘a great big thing of tulle’. Merle was grateful and a dressmaker friend of her mother made Merle’s wedding dress out of the ‘great big thing of tulle’. The wedding dress would later be worn by two of Merle’s sisters-in-laws and four other Wrans.

She and Bob were married in the little Methodist church at Sassafras on 17 June 1944. Merle only had seven days leave. Bob had recently returned from New Guinea and was stationed in Queensland’s north, his unit preparing to deploy to Borneo. For their honeymoon they moved into a guest house in Marysville, Victoria. Bob was taking Atabrine to ward off malaria but instead, he was stricken down with dengue fever.

He spent the first five days of our honeymoon in bed. I spent a lot of days walking around Marysville in the frost and snow, it was freezing.

When Bob recovered, he took Merle out to dinner. The trouble was that half Bob’s gun crew was also staying at the same Marysville guest house and were intent on telling Merle war stories of what had occurred in Africa and the Middle East. Merle was unimpressed and Lance Corporal Hare demanded that such talk finish. His bride was present, and they were on their honeymoon.

Don came down for my wedding in 1944, and that was the last time I saw him, on my wedding day.

Don was a flight engineer/air gunner of Catalina flying boat Catalina A24-203 No.20 Squadron, the ‘Black Cats’ based in Darwin. A detachment of Catalinas took off from Darwin on 1 March 1945 for Jinamoc Island, a small tropical island in the Philippine Sea. On the morning of 7 March 1945, Catalina A24-203 and its crew of nine flew away from Jinamoc and arrived early afternoon at the United States held Lingayen Gulf on the northwestern Luzon Island in the Philippines. After refuelling the aircraft took off at 1630 hours on a mine dropping operational flight over the Pescadores area with an alternative target at Tainan on the west coast of Formosa (Taiwan). No messages were received from the aircraft. It had simply disappeared.

Merle was called into the Cerberus main office and informed that her brother and his crew were ‘missing’, perhaps ‘shot down somewhere’. It was a terrible shock.

It’s the worst thing that has happened to me in my life. I just lay in my bed the whole night, looking out the window. I was absolutely floored.

She was in an emotional fog but there was still a war on. Merle had to return to her duties, however part of her had died; that is what happens when you are a twin.

Correspondence continued from authorities to the Storrie family. The word ‘Missing’ always means a semblance of hope remains. Finally on 9 January 1947 that was extinguished.

It is deeply regretted that it is considered that had your son survived, some news of him would have by this time been obtained and it is considered that all hope of finding any member of the crew alive must be abandoned. The searches by the United States authorities have now been completed and have failed to discover any trace of the aircraft or the crew. It is considered probable that the aircraft had come down into the sea.

Don and his crewmates are commemorated on the Labuan Memorial in Malaysia and the Australian War Memorial.

Merle Hare (Hare)

Merle passed her examinations to be promoted in Petty Officer. She, Bob and Merle’s sister Alva, were in Martin Place Sydney, as the end of the war celebrations raged. ‘Everyone went mad, it was just unbelievable.’

The three of them could appreciate the happiness, that the horrible war was finally over, and Merle felt that relief. However, ‘I had lost my twin brother’ and the tears came ‘knowing he wouldn’t be coming back’.

Merle and Bob made their home in Melbourne where Bob worked as a manufacturers’ agent, for Maryborough Knitting Mills and Clunes. They named their son Donald in honour of Merle’s brother. They also had a daughter Ann. Bob Hare died on 11 December 1997. Life continued, and Merle is the first to admit she has lived a full life. ‘When you get to 100, nothing fazes you anymore.’ Merle Hare (nee Storrie) is treasured by naval veterans, current serving members and Legacy. She was again the centre of admiration travelling in a jeep at the front of Canberra’s 2025 ANZAC Day Parade.

Proud of her garden, Merle Hare (nee Storrie), 105 in April 2025. (Spurling)