KATHERINE STINSON was born in Alabama in 1891. That likely was the least amazing thing she did because her achievements were soon remarkable by world-wide standards. Stinson wanted to go to Europe to study music and return to teach piano. To accomplish this, she needed to earn money, not easy for a 19-year-old girl in 1910. The choices were limited, she could be a teacher, a secretary or a store clerk. Stinson did the sums and worked out she would be 90 before she saved enough to get to Europe. She read a newspaper article about pilots who participated in air shows. Pioneering pilots defied the odds performing daring stunts over vacant fields and earned $1000 US dollars a day. If other people could do it, so could I, she decided. The word ‘crazy’ never entered her mind, what was crazy about becoming a pilot in 1910 to become a music teacher!

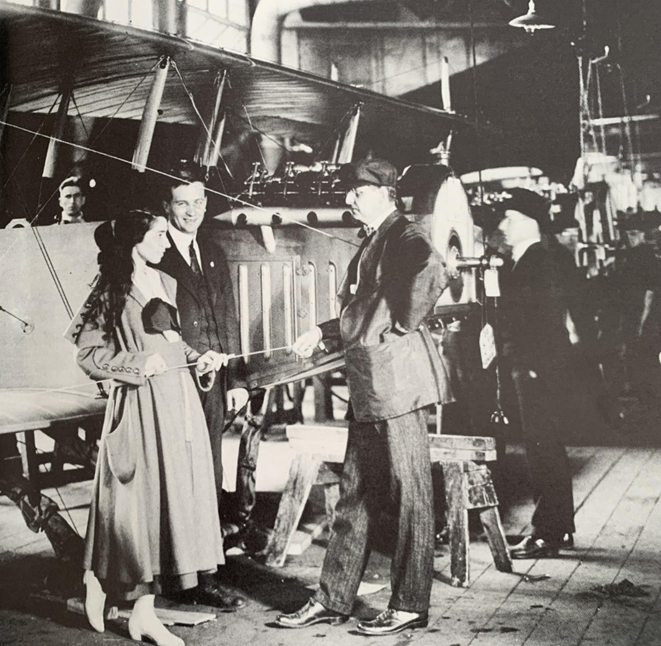

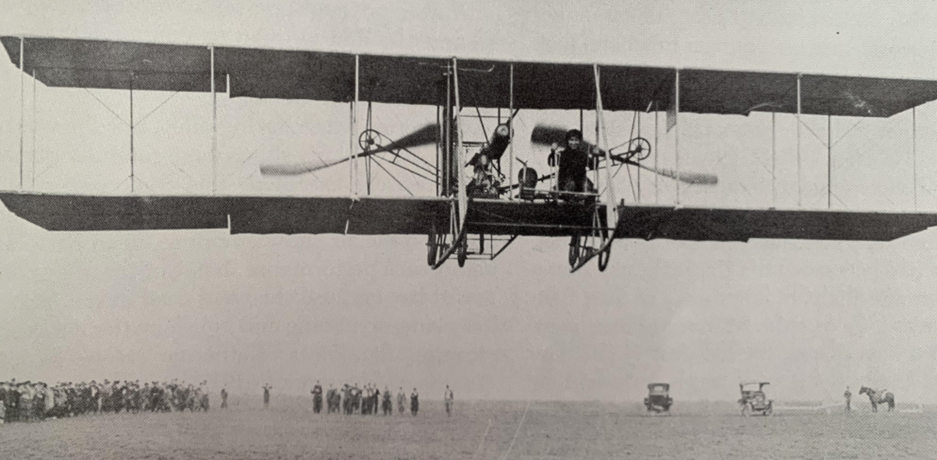

Stinson already knew how to drive a car; how much harder would it be to fly an aircraft? The Wright brothers had only completed their first successful flight, in 1902. Aircraft were fragile wooden frames covered in muslin; the cockpit was like a giant swing with wings attached; with the propeller at the back. The public was very sceptical about projecting oneself up into wide-blue yonder, If God had meant people to fly … that sort of thing. In January 1912 Stinson was a passenger for 20 minutes in the air, it was thrilling. Who would teach her? There were fewer than 200 licensed pilots world-wide, of whom only three were women. She sought out a famous aviator, Max Lillie of Chicago. He took one look at Stinson, a very slight five foot nothing, and said a resounding ‘NO’. He believed the ‘little girl’ would be incapable of managing the two-handled ‘pusher’ aircraft, the two shoulder-high sticks which controlled the height and angle of the wings. The ‘little girl’ proved very stubborn, arguing that perhaps clear thinking, calmness, determination and dexterity, qualities she had in abundance, were more important than strength, size and her sex. After just four hours of flight time Stinson flew alone.

On 12 July 1912 she passed the pilot’s test, becoming the fourth American woman pilot and commenced aerial acrobatics.

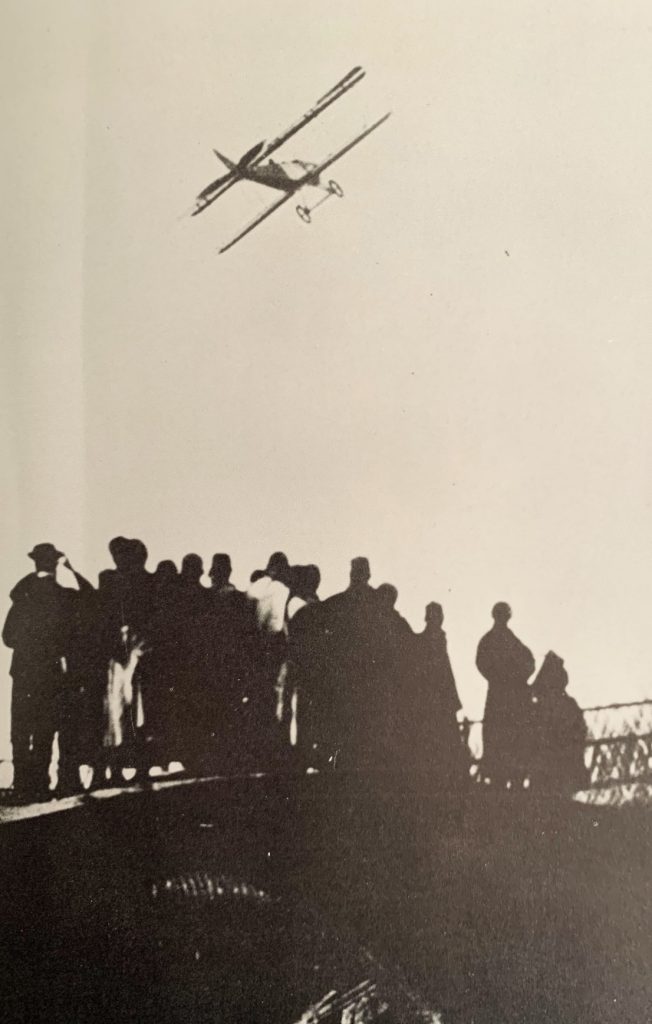

People loved to watch her. There was something exciting about watching this pretty young woman undertake daring stunts in those strange flying machines. They flocked to country fairs to see the ‘Flying Schoolgirl’ soar above them among the puffy white clouds.

Stinson flew through many states, rarely frightened except when lightning threatened.

Her mother Emma decided there was a business opportunity and in 1913 she joined her daughter in founding the Stinson Aviation Company in Hot Springs, Arkansas. They began to build, sell and rent aircraft. The career in music was long forgotten.

Max Lille had persuaded the United States Army to allow him to use the parade grounds of Fort Sam Houston, at San Antonio, Texas, as a flying field and persuaded Stinson to move there. She too delighted in the ideal weather conditions, so her family moved there also. She leased land and established the Stinson School of Flying. Her fame increased when in her Wright Model-B plane she mastered the loop-the-loop considered extremely dangerous as the aircraft could easily stall. If the aircraft was high enough, theory was the pilot could restart the stalled engine. She taught herself and became the first woman to complete the stunt. By the end of six months, she had performed the loop 500 times without accident.

Stinson was a brave pilot but took considerable time to plan the manoeuvres and in cleaning her plane. In 1917 she wrote in The American Magazine:

The men though I was a regular old maid about it. They said I would ruin the cloth with my scrubbing. … I wanted to see the conditions of things under all that dirt. I really did find that a good many wires needed to be replaced. … If your airplane breaks down, you can’t sit on a convenient cloud and tinker with that!

She realised she needed not only to be a good pilot but also a good mechanic. Every time she travelled to an air show she and her aircraft undertook the journey by train which required dissembling the plane for the trip and reassembling it at the destination.

Her fame continued to grow and soon she was performing aerobatics in skies over Canada, Britain, Japan and China. In Tokyo in 1916, 25,000 people stared open-mouthed from below and mobbed her on landing. She was soon being referred to as the world’s greatest woman pilot; newspapers and magazines constantly featured her feats.

When the United States entered World War I the US Army recognizing the importance of aviation called for pilots. Stinson lost no time in volunteering but was told she was a woman, and the Army would not accept ‘a woman’. Bitterly disappointed she flew through the country dropping Red Cross fundraising leaflets and collecting pledges of money for the war effort by performing flying feats. In the nation’s capital she circled the Washington Monument and landed near the cheering crowd, before presenting the Secretary of the Treasury, $2 million in Red Cross pledges.

Stinson was now 26 and decided it was time to attempt a long-distance record. Fellow aviator Ruth Law, had in 1916, set a long-distance record of 512 miles (824km), and this record needed to be broken. A special aircraft was ordered, one with a maximum air speed of 85 miles per hour and capable of travelling 700 miles (1127km) without refuelling.

The record could be undertaken flying from San Diego to San Francisco. On 11 December 1917, her small open-cockpit plane took off into the foggy sky. San Francisco lay 610 miles (982km) away, further than any pilot, man or woman, had ever flown without stopping. Just past Los Angeles the jagged mountains loomed, and the winds became treacherous. The open cockpit meant she was chilled to the bone and as she coaxed the plane to 9,000 feet, higher than she had ever flown, the wind cut her lips.

Visibility was low but she remained calm, and the mountains disappeared. Her map was mounted on rollers, and it was very long. And then there it was, the Golden Gate Bridge. As she circled and found the Presidio Army Fort:

Tears came to my eyes as I heard the cheers of thousands of soldiers down below. They lined up in two files and I landed between them. They rushed up and helped me out of my plane and I was mighty proud.

A cacophony of noise erupted as ships and small vessels crowding San Francisco Harbour blew their horns. There was just two gallons of fuel left in the aircraft’s tank.

Katherine Stinson had flown 610 miles (982km) in nine hours and ten minutes, longer and further than any aviator in the world. She applied for a job as a war reconnaissance pilot but again the Army refused, citing that it would be too taxing for a woman.

There had to be another challenge, so she set out to fly mail nonstop from Chicago to New York. Very strong headwinds meant Stinson ran into trouble and out of fuel and she landed on a mud bank just shy of New York city. The ‘shortened flight’ of 783 miles (1260km) broke her own long-distance record, as well as the American distance and endurance record. Only then did she admit that she had spent five days ill in bed and was weak and suffering from a high temperature when she slowly lowered herself into the cockpit.

If you determine that it shall be your mind, your body will surprise you the way it bucks up and behaves itself.

Stinson then flew mail from New York to Washington, but the war still beckoned.

The expert pilot became an expert ambulance driver, serving in London and in France. Her health suffered and she was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The six-year recovery battle ended her flying career. In 1928 Stinson married Miguel Otero, Jr a war pilot and they became the parents to four children. Not to resign herself entirely to domesticity she studied architecture and became an award-winning home designer. Stinson-Otero continued to encourage people to follow their dreams.

Fear as I understand it, is simply due to lack of confidence or lack of knowledge – which is the same thing. You are afraid of what you don’t understand, of the things you cannot account for. You are afraid to attempt something you believe you cannot do.

Katherine Stinson-Otero died in New Mexico in 1977, aged 86. She never did become a piano teacher, but she was one hell of a pilot and inspiring woman.