It came in the post, and it was wonderful, a pretty lace postcard from a terrible war. ‘A Kiss from France’ for a mother. He remembered her birthday but given the irregular mail and distance the card had to journey around the world Sapper Horace Mervyn Herrod (6672) knew it was unlikely to arrive in time. It was the thought that counted, even late.

If 1915 was known as the ‘blooding’ of Australian military forces on the rocky cliff faces of the Gallipoli Peninsular, the mud and slim of the Western Front was the stage for human carnage. In March 1916 Australian troops arrived and until the end of the year they faced war as none could have imagined. The Battle of the Somme saw British and French forces attacking along a 40-kilometre front as they attempted to break German lines. On 1 July alone around 60,000 British soldiers were killed. By November this battle saw more than a million men from opposing forces slain or wounded. At this time in World War I British forces were hampered by erudite leadership which expected the unachievable against a determined enemy.

The Battle of Fromelles of 19/20 July when the Australian 5th Division attacked German lines near the township was a disaster and in just one night 5,533 Australians were annihilated. What followed was even worse. The Battle of Pozierres between 23 July and 5 September 1916 saw Australian 1st, 2nd and 4th divisions thrown into the costliest battle of the war – more than 23,000 died or were wounded in six weeks. In November the Battle of Fleurs was another costly attack with any gain in territory lost beneath the German counterattack.

The postcard which found its way was adorned in delicate ping and white silk flowers. The lift-up pocket revealed an equally sweet note with flowers and idyllic French rural scene with the notation ‘From your loving son’. The words on the back in pencil ‘9 September. Wishing you many returns of October 21. With Fondest Love From Horace xxxx.’

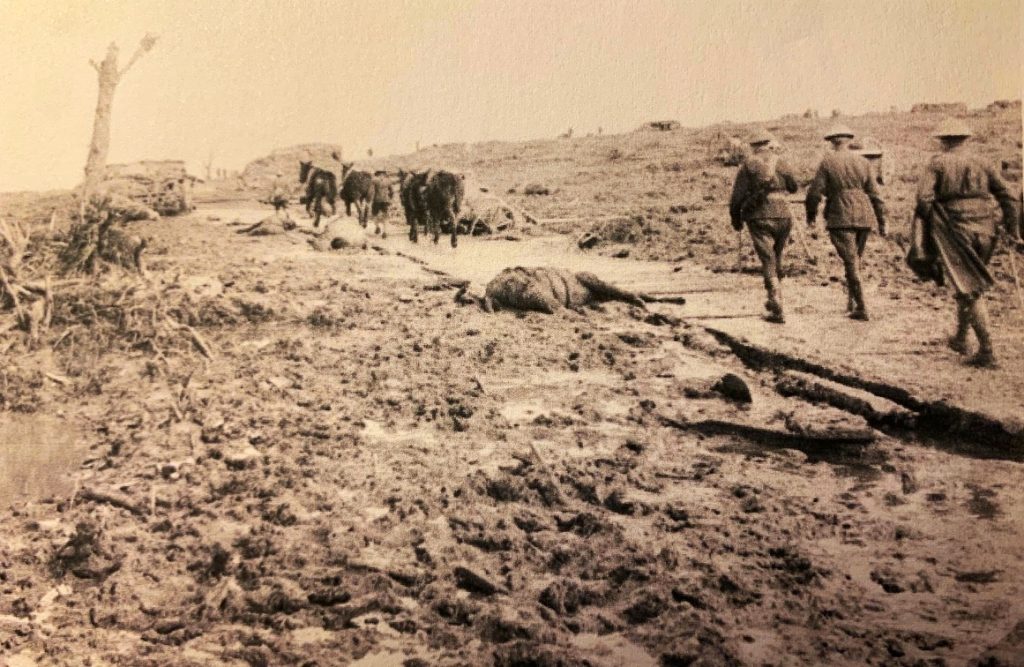

The reality of the situation when Horace wiped the mud from his hands to scribble those words with a tiny pencil, in no way were reflected the sweet delicate card. Sapper Herrod cast his eyes across ground where there was not a flower in sight, nor greenery of any shade. Green required trees and there were none. Those which had not been blasted to oblivion by shell fire had been cut down for walkways over the mud. Horace was attached to Australia’s 7th Field Engineers and all he had seen since his arrival in France was a sea of mud and destruction.

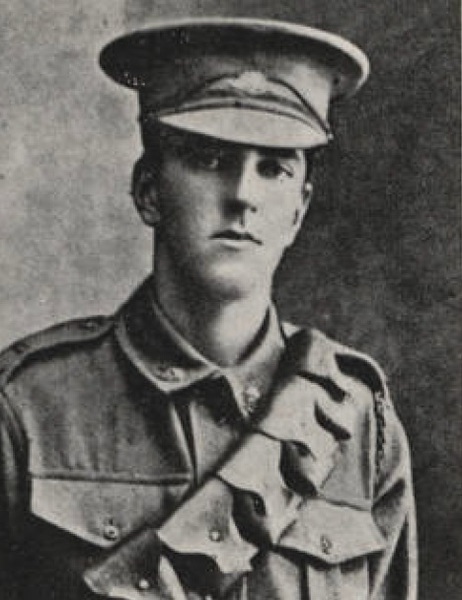

Born in October 1892 Horace Mervyn Herrod was the son of Matilda Hannah and Reuben Herrod. The family lived in the Sydney suburb of Paddington, renown for its close-knit community living in narrow two-storey terrace houses, some decorated with ornate corrugated iron balustrades, some far-less opulent. It is likely Horace and his mother lived in one of the latter because Reuben had died a dozen years before and the son was supporting his mother. They realised how fortunate he was to have gainful employment and as a junior Compositor with John Fairfax&Sons. Setting type, text, and illustrations was satisfying if not a slight dirty occupation, being surrounded by ink and greasy machinery, but Horace was the first in his street to know the news and was an avid reader. Matilda was proud that her son had such an important job given labouring on the roads was the most common occupation amongst the sons of her friends.

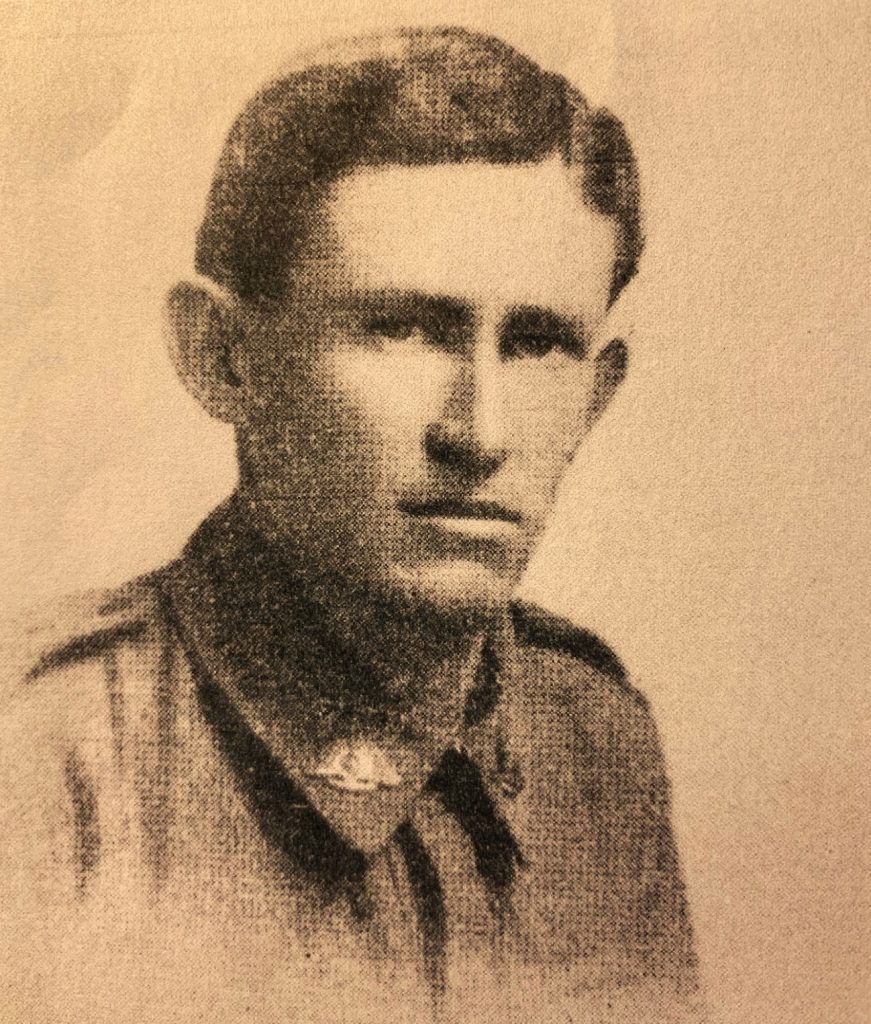

She needed to be careful not to appear overly proud of her boys. Her elder son Victor Lambert (88) had joined the army as soon as he was old enough, to help with the family finances and to ensure Horace had a better start in life. Victor was one of the first to be sent overseas, embarking from Sydney on 18 October 1914. He had already seen too much of war and was now in France as a Quarter Master Sergeant. Victor was pleased that when his little brother enlisted in December 1915 his experience with machinery and intelligence was quickly appreciated so that he was enlisted as a Sapper. If Horace needed to be part of this war better, he was in the engineers than in the trenches. Prior to embarkation Horace ensured that three fifths of his pay was allotted to his Mother.

Horace had not yet arrived in France when Victor was badly wounded in the Battle of Pozieres and Matilda received the telegram she dreaded.

I regret to advise you that No.88 Company Quarter Master Sergeant V.L. Herrod, 1st Btn, has been reported wounded.

For Victor the war was over. By September he was being transported from hospital to hospital, from Rouen to England. By the time Horace was marching towards the front, attached to the 7th Field Company Engineers. Victor was on his way home to Australia his left foot permanently damaged, out of the army and left to make his way in the world as an invalid pensioner.

When the younger Herrod son sent the postcard adorned with pink and white flowers, the 7th Field Company Engineers were working at a frenetic pace undertaking road works in the Albert, Amiens region. Australian sappers erected Nissen huts for ‘parties working on quarry ammunition siding and the 3rd Field Ambulance.’ Horace and his fellow sappers constructed a culvert and box drains under the Longueval Railway Station, the railway itself and surrounding roads. This work felt a little like labouring, but it was helping to win this war. Horses and wagons were used to gather and remove but it was arduous work for the horses as they pulled loads with their hooves sinking deep into the Somme mud. Too much weight for too long on minimal feed meant the bodies of horses were strewn along the sides of the planked roads.

Guillemont was a French town situated about six and a half miles (10.4 kms) east of Albert. The town was levelled by shell fire. Australian sappers may have been equipped with shovels and other construction equipment rather than weaponry, but they completely understood trench warfare and were subjected to the same bombardment. The fighting around Guillemont was bitter between July and August 1916. German forces continued to hold positions and the Allied line split. To ‘straighten the line’ General Sir Douglas Haig ordered the taking and holding of the high ground at Longueval, thus protecting the Allied right flank and permit an advance in the north. German resistance was powerful, and the areas known as Trones Wood and Delville Wood became the killing fields of soldiers from many nations.

A British attack commenced at 6am on 3 September with the bombardment followed at noon by the infantry charge. The push moved further north toward Longueval on a site known as Waterlot Farm (which was a sugar refinery). The shelling never stopped, even when the battle was considered won and or lost. Night shelling was particularly terrifying-the noise, the flashes, and the destruction.

Sapper Horace Herrod saw his first white Christmas and New Year in the trenches of the Somme. At 10.30pm on 8 January 1917 his dugout was shelled. Horace was killed.

Horace was eventually buried in Delville Wood Cemetery, France. In decades to come where he lay reflected the peaceful, pretty, rural French scene, with woods, greenery and delicate flowers as depicted on the silk birthday card he posted to his mother Matilda in 1916.