Victor Charles Friberg was born to Anders and Amelia Friberg of ‘Mootala’, Locksley Road, Ivanhoe, Melbourne, Victoria. The family enjoyed a stable middle-class lifestyle thanks to the furniture manufacturing business Anders had established. Victor entered the family business as an apprentice cabinet maker. Creating beauty out of rough-hewn timber was a noble and satisfying livelihood. Perhaps it was his Germanic name that encouraged Victor to enlist quickly. On 24 August 1915 he signed the attestation form, swearing to:

Well and truly serve our Sovereign Lord the King in the Australian Imperial Force from 24 August 1915 until the end of the war, and a further period of three months thereafter unless sooner lawfully discharged, dismissed, or removed thereafter and I will resist His Majesty’s enemies and cause His Majesty’s peace to be kept and maintained: and that I will in all matters appertaining to my service faithfully discharge my duty according to law. So help me God.

The sentiment was pure, the youthful enthusiasm to serve, to participate in the grand adventure, to travel with mates overseas. Victor was 22 years and three months. His medical was brisk, and he was inoculated against smallpox and enteric fever. He was solid for his age, at 5ft 6inches (1.76 m) and 10 stone 6lbs (66 kgs), a good-looking man with fair hair and blue eyes. By the third day of September his training had commenced with the 7th Reinforcements, 24th Battalion. News of the bloody defeat at Gallipoli dominated Australian newspapers and was of great concern to Anders and Amelia Friberg, but their son was over 21 and like all young men of that age, felt invincible.

They were proud to see their son kitted out in khaki, complete with slouch hat, but this was war, and this was their son. The mixture of emotions was intense as they waved their farewells as HMAT Commonwealth cast its mooring lines on 20 November 1915.

Private Victor Friberg landed in Alexandria and became part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on 24 February 1916. At least he was not destined to be another Middle East statistic and was relieved to embark for Europe, now attached to 8th Battalion (Btn). News sent home offered some relief, France was close to England, France would be safer. Little could they have imagined what their son would face in the ensuing months. Fighting was ferocious, the modern weapons of war wrought shocking injuries. There was no respite, assault upon assault, men falling in startingly numbers for a small piece of ground which was then wrenched back in blood.

On 6 April 1916 Victor posted a handsome silk postcard emblazoned with a soldier’s hat. On the back her wrote:

Dear Mum, just a little card from somewhere in France … Show to Rose. Your ever-loving son Vic.

The card was not addressed to his father because he had lost respect for a man with a wandering eye for other women. Nonetheless, official correspondence continued to be addressed to the father.

Private Victor Friberg was admitted to hospital in June suffering from influenza and pyrexia, a term which was used simultaneously for fever and a nervous condition.

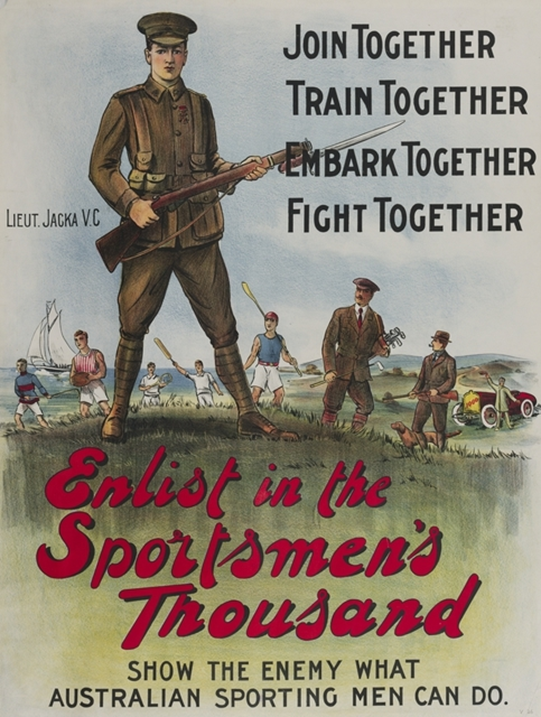

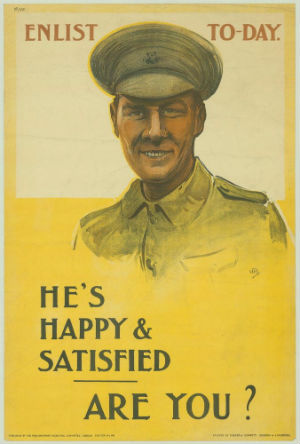

Whatever romantic vision Victor may have had of war and adventure, encouraged by the slick recruiting posters, this was not it.

Day after day struggling to stay alive in trenches deep in water, rats and the dead. Twelve days in hospital was a brief reprieve before he was ‘discharged to duty’ a very innocuous term for what he returned to – the Battle of Pozieres.

The Somme is a gentle river which flows from St Quentin in a lazy loop to Peronne westwards to Amiens through Corbie, The battles within the Somme region, was neither gentle nor lazy, a bloody campaign which raged on the muddy fields of France and Belgium and incurred a million casualties. Over a period of 42 days the Australians made 19 attacks, 16 of them at night; as a consequence, the Australian casualties totalled a staggering 23,000 men, of whom 6,800 were killed.

On 11 September Victor was hit by withering fire. He was stretchered to 10th Casualty Clearing Station, Belgium, with shattered legs and losing blood rapidly. Within the medical tent staff worked at a frantic pace to save what was left of soldiers. The surgeon assessed Victor’s condition and realised it was hopeless, he had to amputate both legs and a thigh and life disappeared quickly from the 23-year-old on the 11 September 1916.

On 23 September 1916 the cable arrived at the Friberg home addressed to the absent father, informing Amelia that Victor was ‘dangerously ill gunshot wound legs and right thigh amputated will furnish progress report when received’.

The shock was terrible, Victor had been hit by shell fragments and his injuries were beyond comprehension. Perhaps there was a moment between the tears that Amelia wondered if it was not for the best that the healthy robust handsome son she remembered did not survive, and she could be forgiven for that.

Telegrams travelled slowly in 1916 and Australian authorities simply could not keep up with the dead and maimed. When Amelia struggled with the news, Victor had already died and been buried. The letter from his superior officer informing her of Victor’s death was dated 13 December 1916, he too struggled with too many letters.

Victor’s possessions arrived in a neat box. It took Amelia and Rose time before they gently explored the contents: identity discs, letters, wallets, pouch, photos, the fountain pen, wristwatch, handkerchiefs, hat badges, a diary, draught pieces and a fork. A pipe caused the vaguest of smiles, they had no idea Victor had taken up smoking a pipe. In January 1920 the Department of Defence sent a photograph of Victor’s grave one of 10,785 World War 1 war dead resting in Belgium’s Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery.