It could be tough growing up in a family of high achievers. Her father was Headmaster at Prince Alfred College, Adelaide. A brother was a Cambridge University, England, graduate and now lecturer in engineering; another brother also a graduate of Cambridge, was taking up a lecturing position in Burma; another brother was a surgeon in London; another brother was a medical doctor, and a sister had graduated with an Arts Degree from University of Adelaide. This was nonetheless the 1890s and women were encouraged to aspire to womanly pursuits if they ventured outside the paternal home at all, particularly in a high society South Australian family.

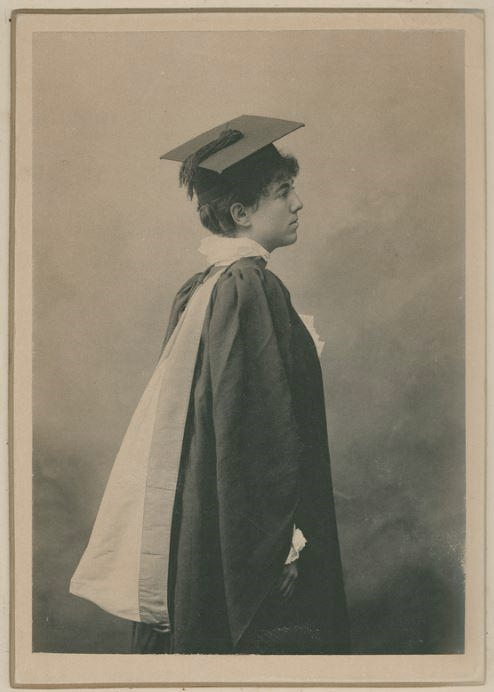

Born in Adelaide on 31 March 1879, the youngest Chapple daughter, Phoebe, from an early age was clearly not going to be restricted by Victorian restraints and preparing for a prestigious society marriage. Her academic aptitude was as quickly obvious. Graduating from the Advanced School for Girls she entered university at just 16 having convinced her parents that she could and should study science.

The Bachelor of Science was achieved in 1898. Inspired by Dr Violet Plummer, Adelaide’s first female medical practitioner, to study medicine, when there was great resistance to women entering the profession; Phoebe was undeterred and won the university prize in her second year. She graduated as a doctor in 1904. Phoebe accepted the position of house surgeon at the Adelaide Hospital. A short period was spent in Sydney where she insisted on working as the medical officer for the Sydney Medical Mission, treating the poor, travelling to their homes by public transport and only charging the cost of the medicine.

On her return to Adelaide while practicing medicine, she agitated for greater opportunities for women and while serving as Honorary Medical Superintendent at the McBride’s Maternity Hospital, Phoebe supported women at the South Australian Women’s Refuge. War broke out a world away, but it would have enormous consequences for Australia and its people. It surprised no one that Dr Phoebe Chapple applied to the Australian Army to enter as a medical doctor.

Australia, unlike Britain and the United States, which formed women’s navy and army auxiliaries, refused to allow women to be attached to the defence forces, in any guise except as nurses. Phoebe became increasingly frustrated as she watched Australian troops transported overseas. By February 1917, 40,000 Australians had already been killed on the Western Front. She decided to subsidise her own voyage to England to enlist in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC).

It was an anxiety, leaving my father and mother, but they, unselfishly, urged me to go – and I felt that the larger duty did call me overseas.

Phoebe was initially appointed as a surgeon at Cambridge Hospital, Aldershot with the honorary rank of Captain and the first woman surgeon to receive equal status to the men.

It was a tremendous experience. I was in the surgical wards in charge of every variety of war ailment and wound. The convoys arrived continually from France and more than 1,000 patients were accommodated at this busy centre.

Although eager to accept her expertise the British Government was not sure she deserved the same status or rank as her male RAMC colleagues. This was overcome by attaching Phoebe to the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMAAC). But women doctors attached to the QMAAC were restricted to examining recruits, running invaliding boards and overseeing the health of serving women. Their uniforms were those of nurses and thus women doctors were reported as ‘nursing service’. It was unsatisfying for a doctor with Phoebe’s qualifications but there was little she could do but conform to the unfair ruling.

By late 1917 the desperate need for medical staff on the Western Front superseded Edwardian conservatism and women medicos were despatched to France on the proviso they should not be in the firing line. The boundaries between bases, and battle zones soon proved impossible to ensure this. Phoebe Chapple was one of two women doctors despatched to the front which she considered ‘an honour for Australia’. In November 1917 she found herself in the centre of the battle zone and described the war at being at a ‘terrible pitch’, with nightly air raids making it so difficult to protect the wounded. ‘We felt so helpless to protect them’.

Despite the conservative predictions that women could not ?? the front-line Phoebe wrote how proud she was of all the female medical staff who:

Behaved splendidly throughout that awful three months in 1918 when nearly every night bombs would be dropped somewhere in the locality.

On 29 May 1918, Captain Phoebe Chapple was at a QMAAC Camp outside Abbeville, which accommodated women working at the British Hospital closely located to the 3rd Australian General Hospital. German aircraft were observed during the day, and they returned to attack at night. The impact was devastating, buildings disintegrated, and one bomb directly hit a trench where members of the QMAAC were sheltering. Hampered by darkness and with the bombing still underway Phoebe moved through the trench to tend to the wounded. She thought little of what she needed to do.

I think when there are suffering and death at hand, fear absents itself. Fortunately, the construction of the trench was zigzag, so the missile was limited in its effect… Out of 40 women, nine were killed outright and a number injured. There was much work to be done then, with limited means, to relieve the sufferers. Even telephone communication with headquarters was temporarily cut off. There were lots more raids, too.

Phoebe considered herself fortunate, she had survived. Authorities believed it was more and she was awarded the Medical Medal (MM) the first woman doctor so decorated. The citation read: For gallantry and devotion to duty during an enemy air raid. While the raid was in progress Doctor Chapple attended to the needs of the wounded regardless of her own safety.

The British Military hierarchy in London reacted, pointing out that the Commander-in-Chief in the Field could not authorise such an award for a woman, female gallantry remained contentious. They favoured that the award be downgraded to, Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE). Authorities finally conceded that the Military Medal was appropriate for Dr Phoebe Chapple. She was surprised, citing she was simply doing her duty as a doctor. Others like Adelaide colleague, Dr Helen Mayo, was incensed by at what she believed to be blatant discrimination. Phoebe was a Captain in the QMAAC, it had never been agreed that women were commissioned, and their rank was never formally gazetted. Had her commission been accredited she would have been awarded the Military Cross.

Had Chapple been an officer (and a man) she would have received the Military Cross.

Fourteen other Australian women doctors travelled overseas during the war to undertake military service. During WWI approximately 150,000 Military Medals were awarded – women represented just 0.1% of that total making Dr Chapple rather exclusive. The second Australian woman doctor recognised for gallantry in the field, under fire was Dr Carol Vaughan-Evans, awarded the Medal for Gallantry following the Rwandan Kibheo massacre in 2005. The Military Cross was not awarded to a woman until 2006 when British Army medic Private Michelle Norris was recognised for her heroism during the war in Iraq.

Phoebe Chapple returned to Adelaide and set up a private practice. She stood for the 1919 Adelaide municipal elections and the editorial of The Advertiser considered her a worthy candidate.

She has a wonderfully good record in connection with the war, having displayed administrative talents which should enable her to render excellent service as a councillor if elected. Previous attempts to capture seats in the City Council for ladies have proved unsuccessful, but in principle there is nothing against them; on the contrary, a strong case can be made out in favour of utilising the special gifts of women.

Enough voters did not agree, and Chapple was not elected. In 1921 she took the position of honorary medical officer at the night clinic at Adelaide Hospital where she treated women with venereal disease, a significant post-war health problem. She also held the post of honorary doctor at the Salvation Army maternity hospital for unmarried mothers. Her work with the Adelaide ‘underbelly’ and the trust placed in her by the courts meant she frequently gave evidence in cases involving backstreet abortion and police violence.

Throughout the decade she fought to remove barriers against women entering medicine and was sent to Edinburgh, Scotland to represent Australia at the Medical Women’s International Association Conference to discuss those obstructions. She also visited clinics in Budapest, Vienna and Berlin. In 1953, Phoebe was invited to attend the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in Westminster Abbey.

She continued to practice medicine from her Adelaide home until 85. Dr Phoebe Chapple died on 24 March 1967 aged 87 and was given a funeral with full military honours by the Australian Army, an army which had refused her entry in WWI.